EEG/QEEG Instrumentation

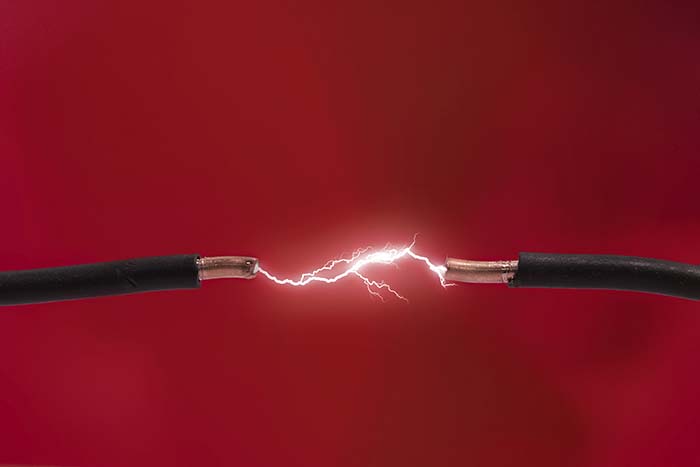

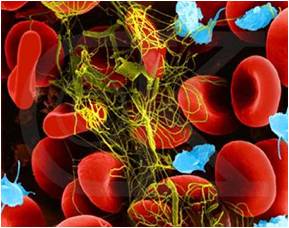

Electricity makes most biofeedback applications possible. Biological signals like skeletal muscle and cortical voltages are streams of charged atoms or molecules called ions. The hardware that monitors these signals is powered by batteries or wall outlets that supply currents of electrons. Graphic © Vladimir Popovic/iStockphoto.com.

Without a basic understanding of electricity and the circuits used in biofeedback instruments, we might mistakenly accept readings produced by equipment misuse or breakdown. "Garbage in, garbage out."

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses III. EEG/QEEG Neurofeedback Instrumentation (2 hours). This unit covers Essential Terms and Concepts, Signal Acquisition, Signal Processing, Aseptic Techniques, and Instrumentation Demonstration.

A. ESSENTIAL TERMS AND CONCEPTS

This section covers A. Essential Terms and Concepts, EEG Recording, and Safety Precautions.

Building Blocks of Matter

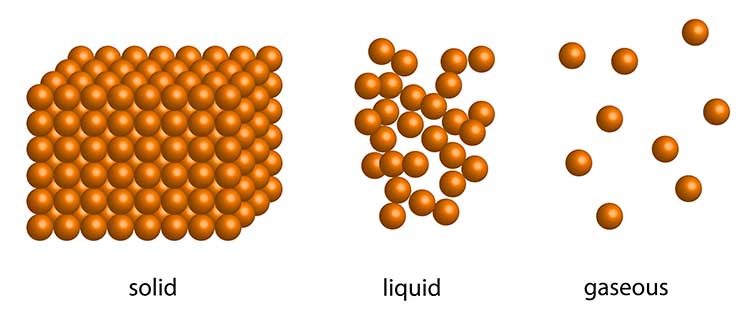

The matter comprising our universe occupies space and possesses mass. Matter can assume solid, liquid, gaseous, and plasma states. Graphic © magnetix/Shutterstock.com.

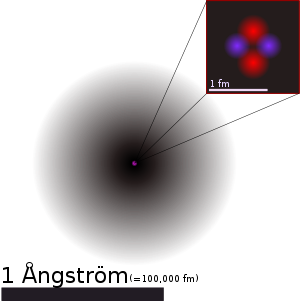

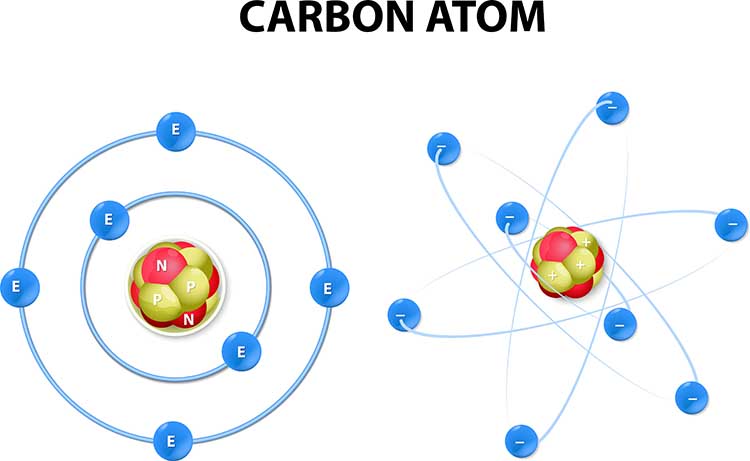

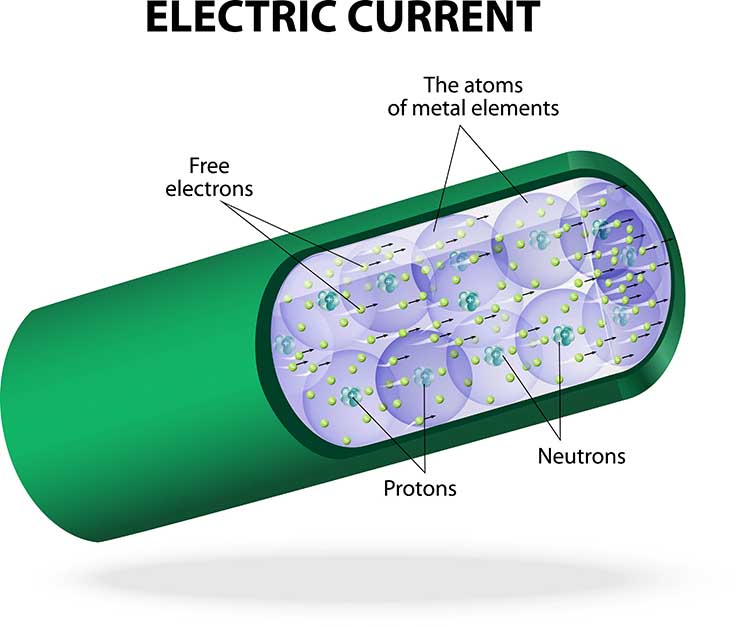

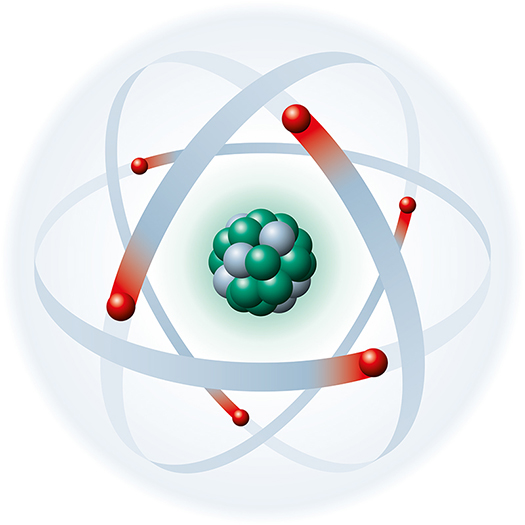

Atoms are basic units of matter consisting of a central nucleus that contains protons and neutrons and orbiting electrons.

The positively charged nucleus contains most of an atom's mass in the form of positively charged protons and uncharged neutrons. Each proton carries a positive charge that is equal and opposite to the electron's negative charge. Negatively charged electrons rotate around the nucleus at varying distances and participate in chemical reactions. The number of electrons equals the number of protons in an atom, balancing the electrical charge of the nucleus. In other words, an atom’s net charge is zero, and an atom is said to be neutral. Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com depicts a carbon atom.

>

Elements are substances that contain identical atoms and cannot be reduced by common chemical reactions. Of the 118 elements confirmed to date, calcium (Ca), carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), and phosphorous (P) are most important to human life (Grant, 2015). Calcium (Ca), chloride (Cl), potassium (K), and sodium (Na) are critical to generating physiological potentials like the EEG. Elements are neutrally charged since their atoms contain an equal number of protons and electrons. Graphic © Designua/ Shutterstock.com.

How does a carbon atom differ from a sodium atom? The difference lies in the number of protons located in the nucleus. A carbon atom has 6 protons, while a sodium atom has 11. The total number of protons determines the atomic number. The number of protons and neutrons approximates the atomic weight.

Ions are atoms or molecules charged by the gain or loss of electrons. The biological potentials produced by cortical neurons (EEG), eccrine sweat glands (EDA), and skeletal muscles (SEMG) are currents of ions. The ions most responsible for these signals are chloride (Cl-), potassium (K+), and sodium (Na+).

Electric Current

Charge (Q) indicates the imbalance between positively and negatively charged particles in a given place or between two locations. Charge is measured in coulombs.

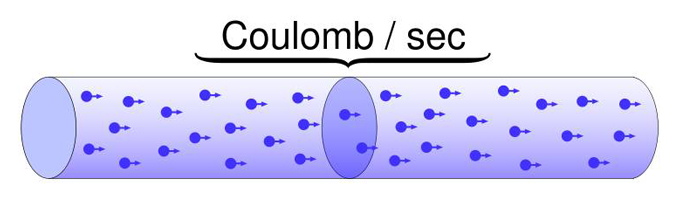

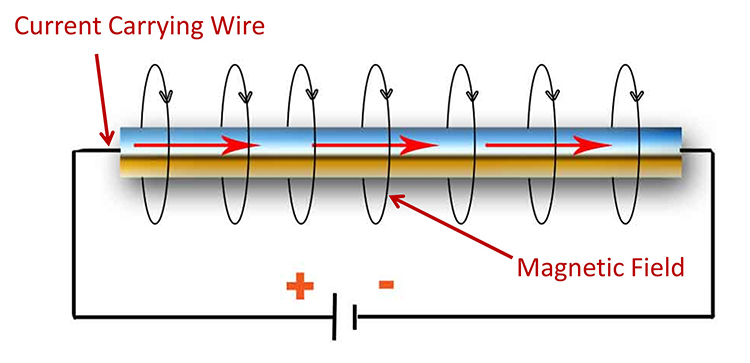

Current (I) is the movement of electrons through a conductor. Current flows because atoms and molecules contain two types of electrical charge: positive and negative. Opposite charges attract while identical charges repel each other. When there is a difference in the overall charge of atoms between two points—for example, between two ends of a wire—negatively charged electrons will flow toward the positively charged end of the wire, creating an electric current.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Current © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

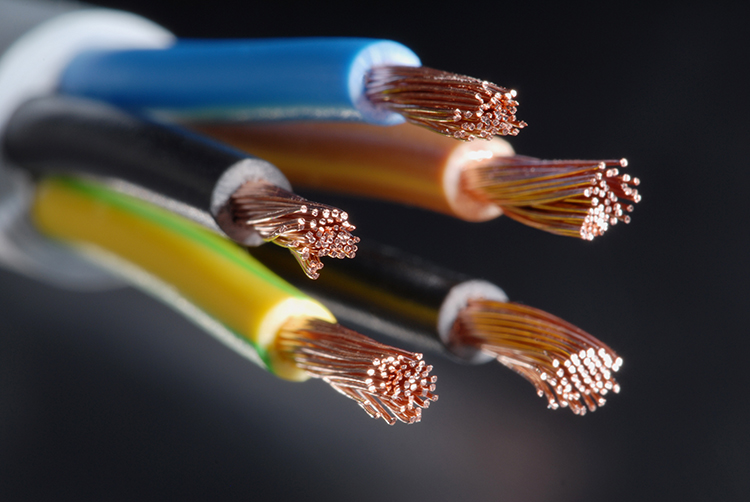

Electrons are also affected by the materials in their path. Conductors like copper allow electron movement, while the insulators enclosing the wires oppose their movement.

Listen to a mini-lecture on Conductors © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © demarcomedia/Shutterstock.com.

Conductors and Insulators

Biological signals like the EEG travel through interstitial fluid,

which is the fluid between the cells in our bodies. Signals like the EEG bump their way

through body fluids as a current of colliding ions (not electrons) until they reach the skin. This process, called volume conduction, allows us to eavesdrop on the scalp's cortical potentials instead of inserting electrodes inside the brain. Electrodes are specialized conductors that convert biological signals like the EEG

into currents of electrons. Surface EEG electrodes function like an antenna to detect the EEG signals produced by

macrocolumns of cortical neurons. Currents of ions, atoms with positive or negative charges, volume conduct to the

scalp (like an FM radio broadcast), and electrodes convert this signal to a current of electrons (Stern et al., 2001). Graphic © Zyabich/Shutterstock.com.

Insulation from body fat, connective tissue, and the epidermis (outer skin layer) interferes with ion current flow and can significantly reduce surface EMG readings. Like the rubber covering the wiring of a muscle electrode, insulators block the flow of electric currents. In natural and fabricated insulators, a large number of electrons in their final energy level produces a cohesiveness that resists electron loss due to collision. The best insulators, like rubber, possess the maximum number of outer-level electrons (Nilsson & Riedel, 2008).

Measuring Current

When we measure current, we learn how much "x" has passed by a point over a fixed period. The "amount" of electric current is measured in amperes (A). You have used 1 ampere of current when 1 coulomb (6.24 x 1018 or 6 billion billion electrons) has passed a point in 1 second (Kubala, 2009).

DC and AC

Electricity travels as either a direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC). Direct current (DC) is the flow of electricity in one direction—from negative to positive. A difference in electrical potential pressures electrons to move. The negative end of a wire repels electrons (e-) while the positive end attracts them. Biological signals representing peripheral blood flow (blood volume pulse and skin temperature), respiration, and skin electrical activity are all DC signals.When we plot DC signals against time, they never completely reverse direction over a second. The electroencephalogram (EEG) contains both DC (slow cortical potentials) and AC (slow cortical potentials and delta through 40-Hz) waveforms. BioGraph ® Infiniti blood volume pulse (BVP) display.

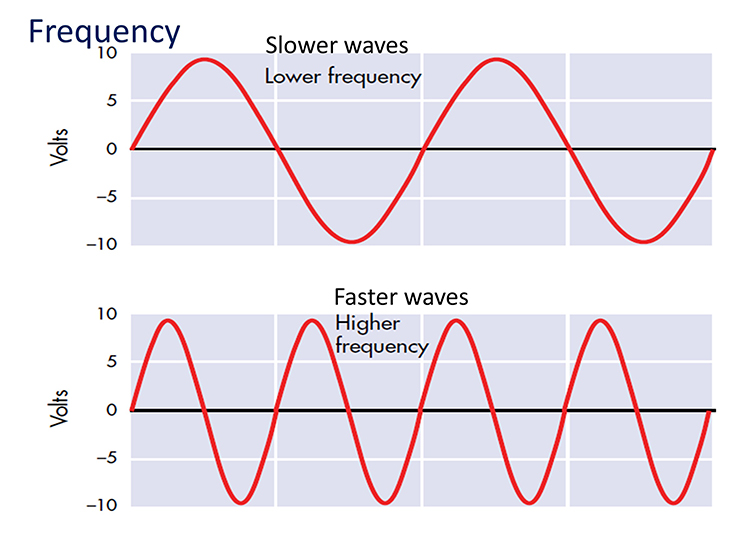

In the space of a second, an alternating current (AC) regularly reverses direction 50 or 60 times. The frequency of an alternating current is the number of cycles completed per second or hertz (Hz). Electrical potentials detected from the cerebral cortex (EEG), heart (ECG), and skeletal muscles (SEMG) all contain AC waveforms (Kubala, 2009). Check out the YouTube video AC and DC Differences.

BioGraph ® Infiniti 60-Hz artifact display. The software uses an auto-scale feature to keep the fluctuating signal on the screen.

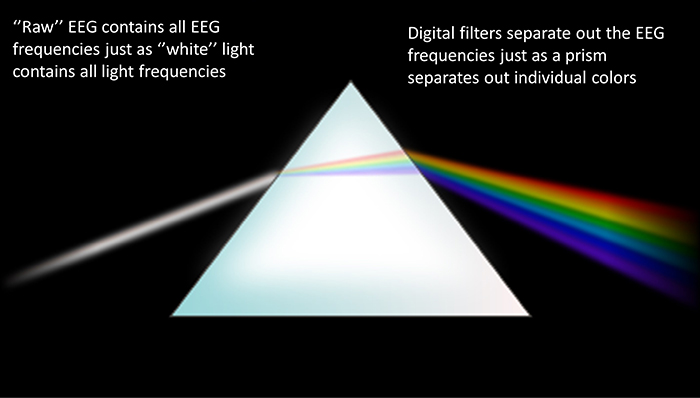

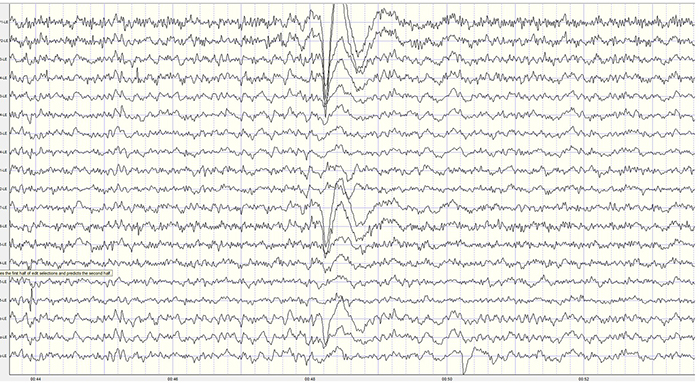

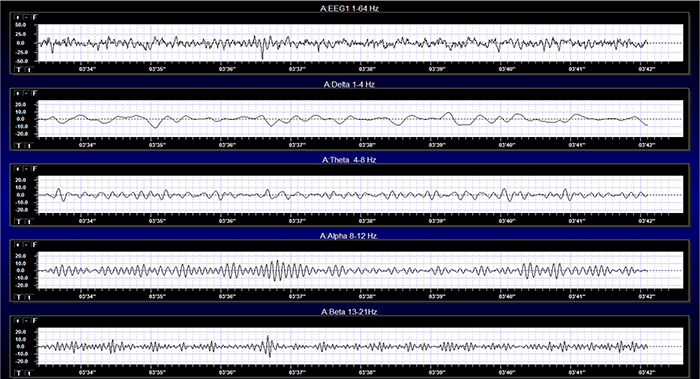

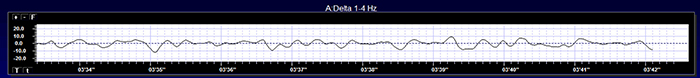

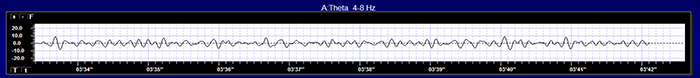

The movie below is a single channel BioTrace+ /NeXus-32 display of EEG activity from 1-64 Hz activity broken into component delta, theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands by digital filters © John S. Anderson.

Electromotive Force (EMF)

What forces electrons to move through a circuit? Electrons flow when there is a difference in electrical potential or charge. A flashlight works because its battery contains negative and positive poles. These two regions of opposite charge produce an electrical potential difference called the electromotive force (EMF) that drives the current ahead. The electrical potential difference can be considered the "strength" of the current. A battery's negative pole repels electrons (e-) while its positive pole attracts them, resulting in current flow. If the battery's two poles had identical charges, instead, electrons would stay put. No potential difference, no current, and no light (Nilsson & Riedel, 2008).Note the negative and positive poles of the circuit that cause the current to move through the wire below.

Voltage

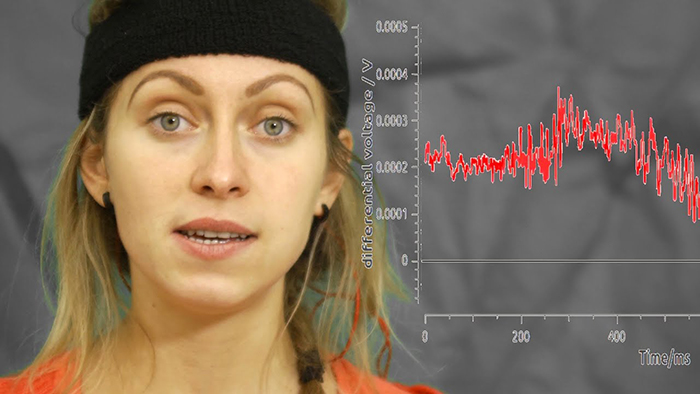

The pressure a battery exerts on electrons flowing through a flashlight is measured in volts (E). A typical flashlight battery is rated at 1.5 volts. One volt is the potential difference required to make 1 coulomb (6.24 x 1018 electrons) perform 1 joule of work. Voltage indexes signal power (Nilsson & Riedel, 2008).When monitoring biological signals, you will record signals ranging from microvolts or μV (millionths of a volt) to millivolts or mV (thousandths of a volt). EEG and SEMG amplitudes are measured in microvolts (μV) and are usually less than 100 μV.

In neurofeedback, clinicians and researchers increasingly express the quantitative EEG (qEEG) signal strength, digitized statistical brain mapping using at least a 19-channel montage to measure EEG amplitude within specific frequency bins, in picowatts (trillionths of a watt).

Watts

An electric current’s overall power depends on the amount of current flowing through a circuit (measured in amperes) and the electric potential driving it (measured in volts). Electric power is measured in watts (W). One watt is equal to one ampere moving at one volt. Multiplying amperes by volts produces the number of watts. For example, an appliance that uses 10 amperes and runs on 115 volts consumes 1150 watts of power (Kubala, 2009). Below are 21- and 32-channel Mitsar amplifier systems featured on the NovaTech EEG website.

Resistance

The electrons moving through a conductor encounter opposition which reduces current flow. This phenomenon is called resistance (R) in DC circuits and impedance (Z) in AC circuits and is measured in ohms (Ω). Resistance depends on the number of electrons found in an atom's outermost energy level.Listen to a mini-lecture on Resistance and Conductance © BioSource Software LLC. Graphic © Peter Hermes Furian/Shutterstock.com. Electrons are red, protons are green, and neutrons are gray.

Increasing the numbers of electrons in this level binds these electrons more tightly together. This cohesiveness reduces the loss of electrons due to collisions with free electrons. The graphic below © Signals.com.

Resistance is a practical concern in biofeedback. Biological signals compete with stronger false signals for a biofeedback instrument's attention. Clinicians clean, abrade and apply conductive gel to their clients' skin when monitoring the brain (EEG) and skeletal muscles (SEMG). Since dead skin, oil, and dirt block biological potentials from reaching electrodes, these precautions improve signal reception.

Dry electrodes like BrainMaster's Freedom 20R do not require time-consuming skin preparation and the application of conductive paste.

Skin resistance is also a biological signal, in its own right, that reflects emotional and cognitive processes. Clinicians measure skin resistance level (SRL) by running an AC or DC across the inner surface of the fingers or palm. SRL is expressed in Kohms of resistance per cm2. Typical values range from 0-500 Kohms/cm2. Lower values reflect more intense sweat gland activity since moisture reduces resistance.

Conductance

Resistance and conductance are mirror images of each other. Resistance is the reciprocal of conductance. Where resistance measures the opposition free electrons encounter, conductance (G) indexes how easily they travel through a conductor like copper or silver. The grraphic depicts resistors in a computer circuit © Kovakchuk Oleksandr/Shutterstock.com.

Resistance is expressed in ohms (Ω). Conductance is now measured in Siemens and was previously measured in mhos (mho is ohm spelled backwards). Skin conductance is one index of eccrine sweat gland activity.

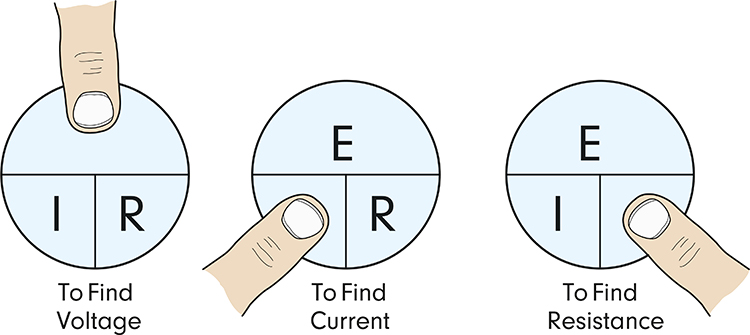

Ohm's Law

Ohm’s law states that the “amount” of current (I) flowing through a conductor is equal to the voltage (E) (the “push”) divided by the resistance (R). These values are measured in amperes, volts, and ohms, respectively (Nilsson & Riedel, 2008).Ohm’s law can be used to find any value in a DC circuit: Voltage (E) = current (I) x resistance (R). Graphic © Emre Terim/Shutterstock.com.

For example, using actual units, 10 volts = 2 amperes x 5 ohms. Check out the YouTube video MAKE Presents: Ohms Law.

Ohm's law is helpful because it describes the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance. We can use this law to show two ways used to detect adequate voltages.

First, if voltage (E) = current (I) x resistance (R), then we can increase the voltage by increasing current or resistance. Hardware designers use this relationship to increase the voltage reaching an electroencephalograph. When EEG voltages (current) enter an electroencephalograph's amplifier, they are dropped across a network of resistors (resistance). This large differential input impedance increases the EEG voltage seen by an electroencephalograph, which helps separate EEG voltages from artifacts.

Second, we can restate Ohm's law from the standpoint of current. If current (I) = voltage (E) / resistance (R), then we can increase current by increasing voltage or reducing resistance. This relationship is the reason clinicians prepare the skin when monitoring the EEG. Skin abrasion and application of conductive gel/paste minimize resistance. This increases the current reaching EEG electrodes, which helps an electroencephalograph distinguish EEG activity from artifacts.

Impedance

In AC circuits, current periodically reverses direction. This introduces frequency, the number of cycles completed each second. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz). When an AC travels through a circuit at a given frequency, it encounters a complex form of opposition called impedance (Z), measured in ohms (Ω). Impedance reduces current flow between electrodes and the brain surface.

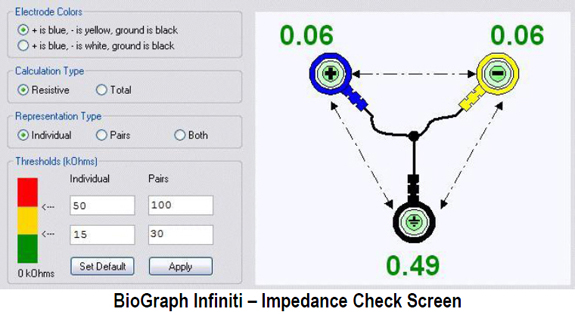

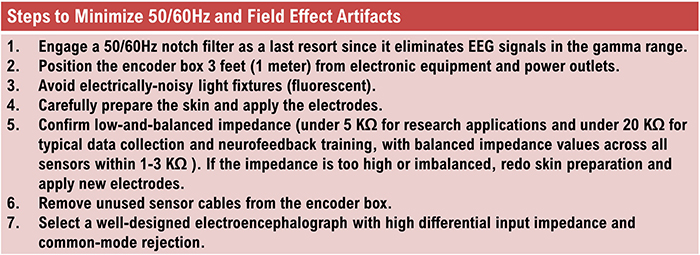

Clinicians perform an impedance test to determine whether they have correctly cleaned and abraded the skin and applied electrodes with sufficient gel or paste (Andreassi, 2007). Excessive impedance means that a weak biological signal must compete at a disadvantage with false electrical signals like power line artifacts. This could contaminate the EEG signal so severely that the electroencephalograph displays power line fluctuations instead of cortical activity.

We measure skin-electrode impedance by passing an AC through pairs of electrodes. An impedance test can be manually performed with a separate impedance meter (AC). Graphic from the bio-medical.com website.

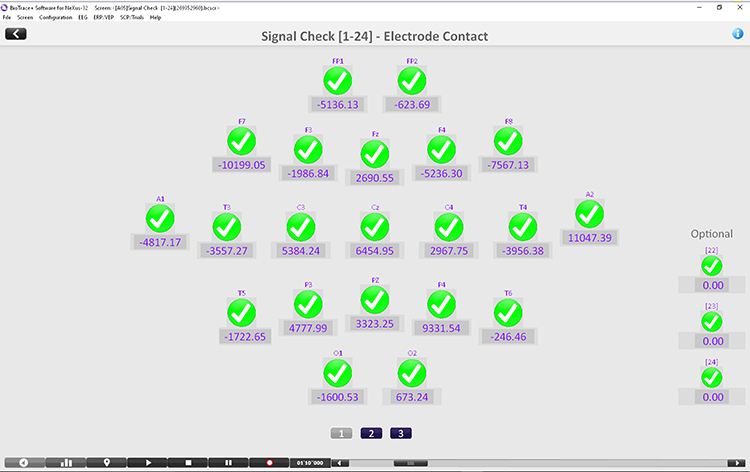

An impedance test may also be performed by software integrated with a data acquisition system and sensors.

After the practitioner has positioned all electrodes, they should check their impedances or offsets using methods appropriate for their equipment. Electrodes that show excessive values can be reapplied after removing them to prepare the electrode site again, if necessary.

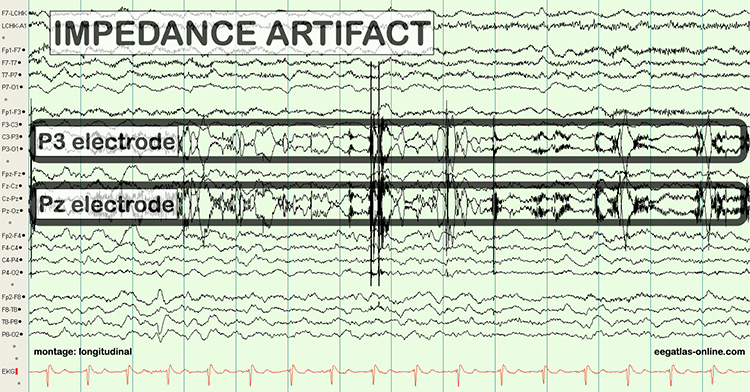

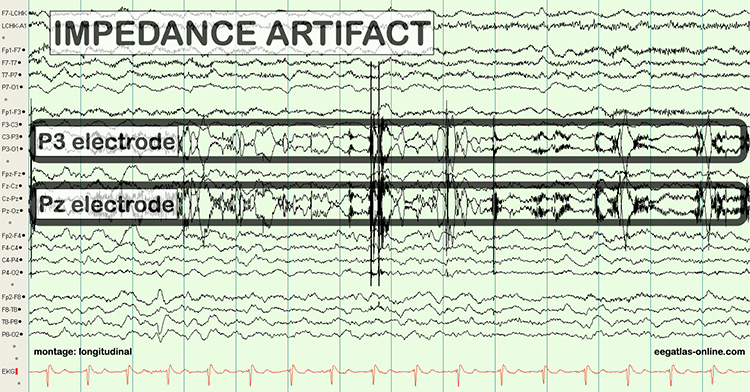

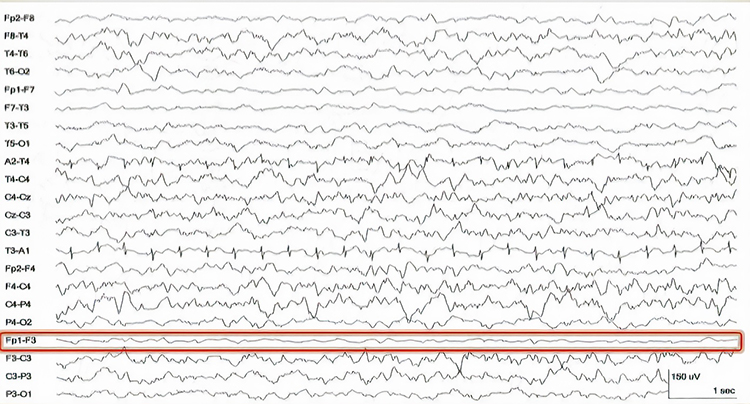

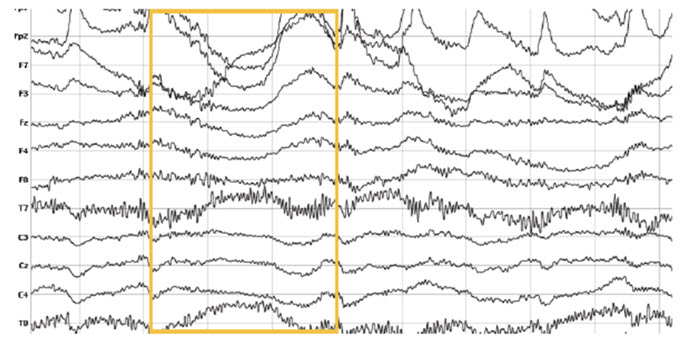

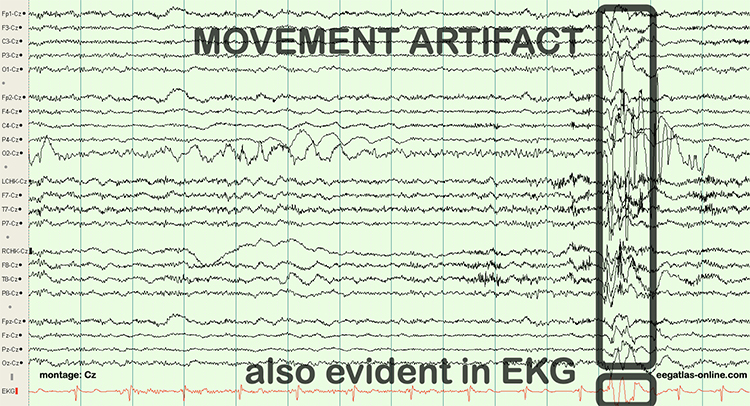

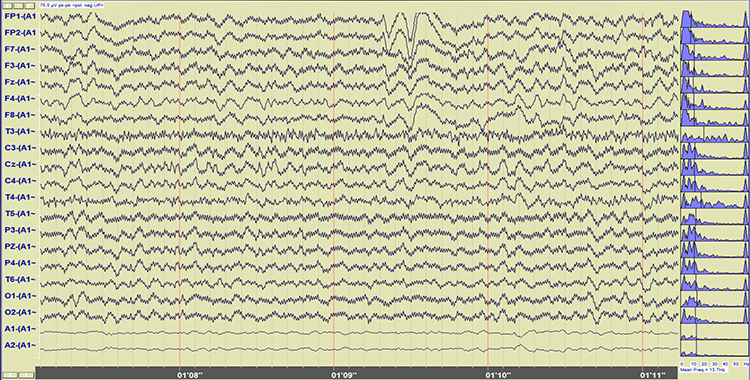

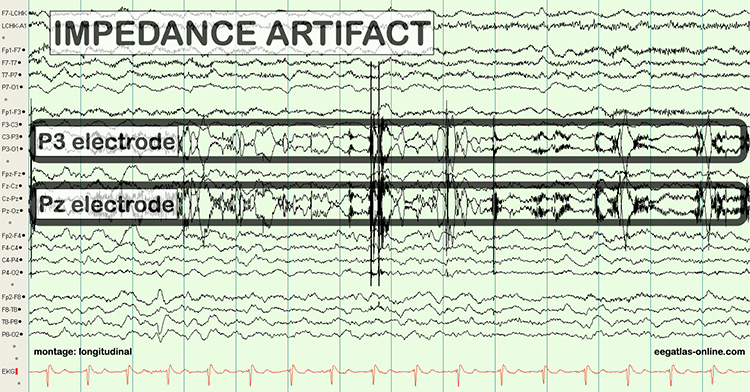

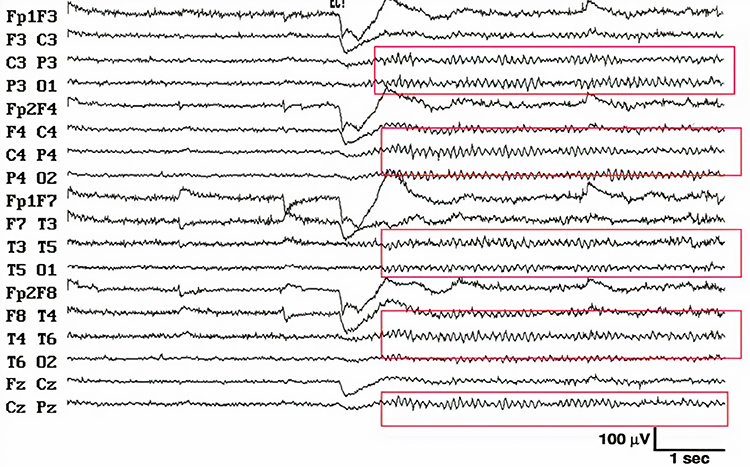

Unless skin-electrode impedance is low (under 5 KΩ for research and 20 KΩ for training) and balanced (under 1-3 KΩ ), diverse artifacts like 50/60 Hz and movement can contaminate the EEG signal, as seen in the P3 and Pz electrodes. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

When the skin-electrode impedance at two sites is unequal, the resulting signals will appear to have different amplitudes when they reach the amplifier, regardless of the actual values. Unbalanced impedance will also increase DC offset values due to the battery effect. The amplifier will boost the resulting inaccurate input, which will be displayed to your client.

When a clinician fails to ensure low and balanced impedances at the start or during a training session, feedback regarding signal amplitude within specific frequency bands will be inaccurate. The wrong thresholds may be selected.

Michael and Lynda Thompson provided an example of an impedance problem that developed during a session because a hyperactive child scratched his ears, resulting in high and imbalanced impedances. Following corrective action that restored acceptable impedance values, high-beta activity (24-32 Hz) declined from 10-15 to 4 μV, gamma activity (45-58 Hz) declined below 2 μV, and SMR and beta activity returned to previous session values (Thompson & Thompson, 2015, p. 66).

DC Offset

DC offset is a voltage that results from combinations of factors, including electrode and gel/paste materials, interactions with skin, environment (humidity and temperature), and sweat gland activity due to stress level. The DC offset value should be consistent across all sensors and less than 25,000 μV, ideally below 10,000 μV. DC offset graphic © John S. Anderson.

Ohm's Law for AC Circuits

We can extend Ohm's law to AC circuits by substituting impedance (z) for resistance and using lower case letters for voltage and current. The revised expression is voltage = current x impedance (e = i x z). This means that voltage is the product of a current flowing across an impedance. In actual units, 50 volts = 10 amperes x 5 ohms.Open and Closed Circuits

Broken electrode cables are a significant cause of equipment malfunction since they prevent electron movement. Clinicians perform a continuity test to check if a cable is damaged. An impedance meter sends an AC signal down the cable to measure opposition to current flow. If there is a break, there is no continuity, and the circuit is described as open. Impedance will be infinite since current cannot flow across space.A blown fuse illustrates an open circuit.

A filament in a fuse melts to create an open circuit when the current exceeds safe values. Graphic © AlexLMX/Shutterstock.com.

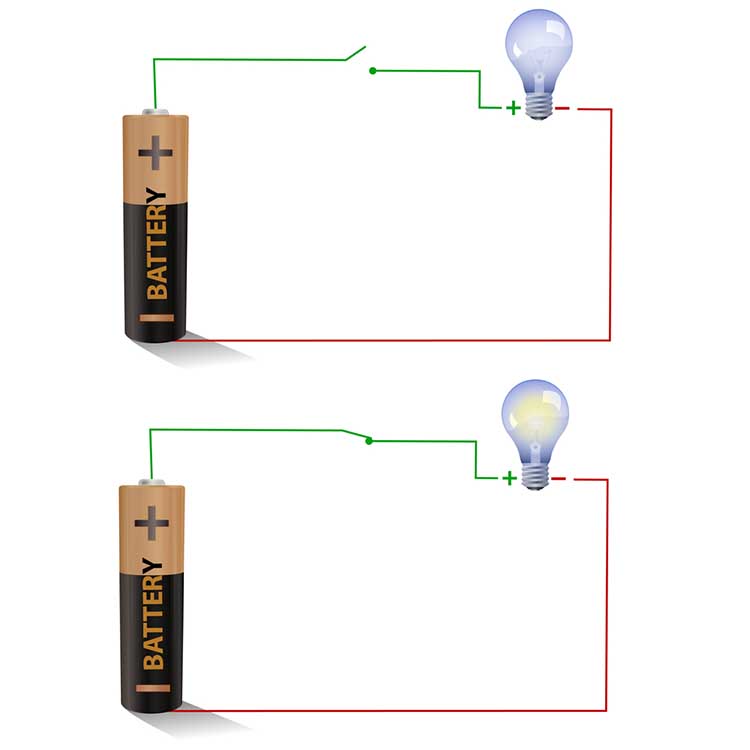

If the cable is free of breaks (continuous), the circuit is described as closed instead. Impedance will approach 0 Kohms since the current can easily travel through the circuit. Graphic © imagedb.com/ Shutterstock.com. The top diagram depicts an open circuit (light bulb off), while the bottom diagram shows a closed circuit (light bulb on).

Behavioral tests, also called tracking tests, check whether the circuit is closed and evaluate the performance of the entire data acquisition system.

For example, when monitoring EEG activity, a clinician can test the performance of the entire signal chain (EEG sensor, differential amplifier, gain amplifier, cable, encoder, and computer) by asking a client to close and then open the eyes. If the computer display mirrors these actions, the behavioral test has been passed, confirming no breaks in the cable.Short Circuit

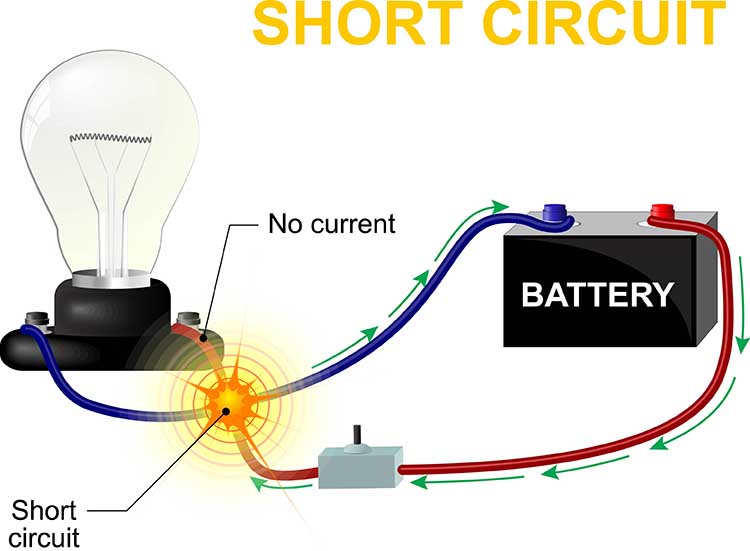

A short circuit results when an unintended connection is made between two points of a circuit. Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

The new path has lower resistance than the original circuit and should measure close to 0 Kohms on an impedance meter. The reduced resistance draws electrons through the short and may increase current flow to levels that can melt circuitry and injure clients (Nilsson & Riedel, 2008).

Visualize a bare wire inside an electroencephalograph touching its metal case. The AC powering this equipment could leak through the metal case and injure anyone touching this surface.

Preventing Signal Contamination

Physiological signals are pretty small compared to surrounding electromagnetic “noise.” They need to be amplified to be distinguishable from background noise.Physiological monitoring requires high-quality connections between the subject and the electronic device. The quality of that connection determines the quality of the signal (information) gathered from that connection. Connections that are of poor quality, for whatever reason, produce poor quality (contaminated) information.

Many factors affect connection quality. These connection points include the skin surface, conductive gel or paste, sensors, and connecting wires.

EEG Recording

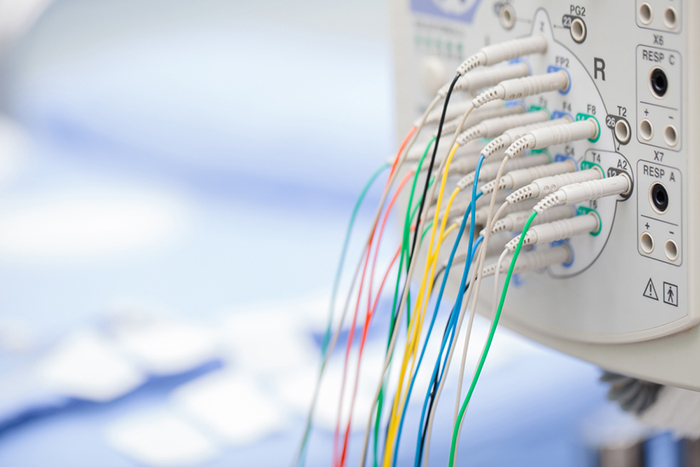

Electrodes

Electrodes detect biological signals. They are also

transducers since

they convert energy from one form to another. Four types of EEG electrodes are shown below: gold cup, gold flat, silver cup, and silver/silver-chloride ring.

Cap systems like the pictured EEG cap share a connector containing a pin or other type of connector for each electrode. These connectors plug all electrodes into the amplifier at the same time.

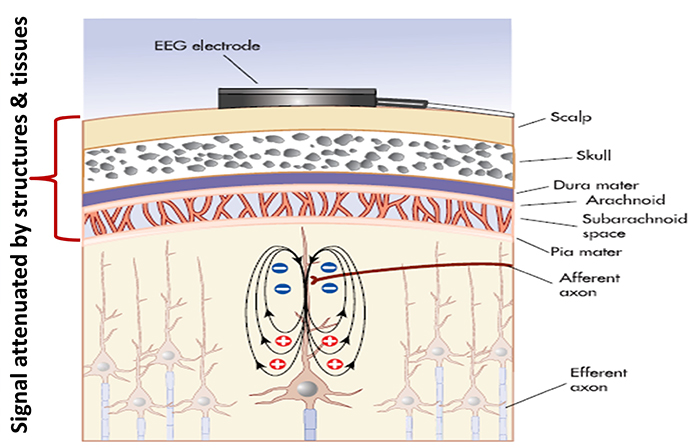

Consider how EEG electrodes work. In response to chemical and electrical synaptic messages, the dendrites of cortical pyramidal neurons develop excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSPs) and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) that travel about 10-12 centimeters as a current of ions through the cortex, blood vessels, glial cells, interstitial fluid, meninges, and skull to electrodes located on the scalp. This

process is called volume conduction. The photomicrograph below shows the interstitial fluid surrounding tissue through which graded potentials propagate.

Electrodes transform this current of

ions into a current of electrons that flows through the cable into an

electroencephalograph’s input jack.

The EEG signal is attenuated during volume conduction. The volume-conducted signal that

reaches EEG electrodes is measured in

microvolts or millionths of a volt.

How do EEG electrodes work? When an EEG electrode is filled with a conductive gel or paste, the electrode metal donates ions to the electrolyte. In

turn, the electrolyte contributes ions to the metal surface. Electrodes create a DC voltage between the electrode metal and the electroconductive gel or paste. Signal

conduction succeeds as long as electrode and electrolyte ions are freely

exchanged.

Recording Problems

Conduction breaks down during polarization when chemical reactions produce separate regions of positive and negative charge where the electrode and gel make contact. DC flows across the connection between an electrode and the scalp. The current carries positive ions to the more negative region of this junction and negative ions to the more positive region. This build-up of ions polarizes the electrode to favor current flow in one direction and resists flow in the other.When an electrode is polarized, ion exchange is reduced, and impedance increases, weakening the signal reaching the electroencephalograph. This problem can result from routine clinical use. Electrode manufacturers control this problem by using silver/silver-chloride or gold electrodes that resist polarization.

Bias potentials are a second potential recording problem. They result from the exchange of metal ions donated by the electrodes and electrolytes in the absence of a biological current. Bias potentials can be prevented by using electrodes with intact surfaces and identical materials (e.g., all gold or silver).

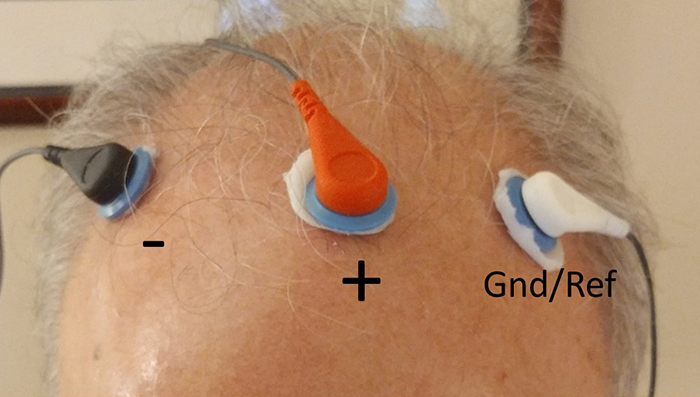

Recording the EEG with Three Leads

We record scalp electrical activity using three recording electrodes: active, reference, and ground. We place the active electrode over a scalp site that is an EEG voltage source. We can locate the reference electrode over the scalp or neutral, but not electrically inactive, sites like an earlobe or the mastoid bone. Finally, we can place the ground electrode on an earlobe, mastoid bone, or the scalp (Demos, 2019). The ground electrode is grounded to the amplifier.Active and reference sensors are identical in construction and are each balanced inputs. They are interchangeable! However, some technologies require that you designate a sensor as a reference. For example, linked ears reference.

In the graphic below, the active (+) is red, the reference (-) is black, and the ground electrode (Gnd/Ref) is white.

The voltages of the active and reference inputs are based on the ground.

EEG Apparatus

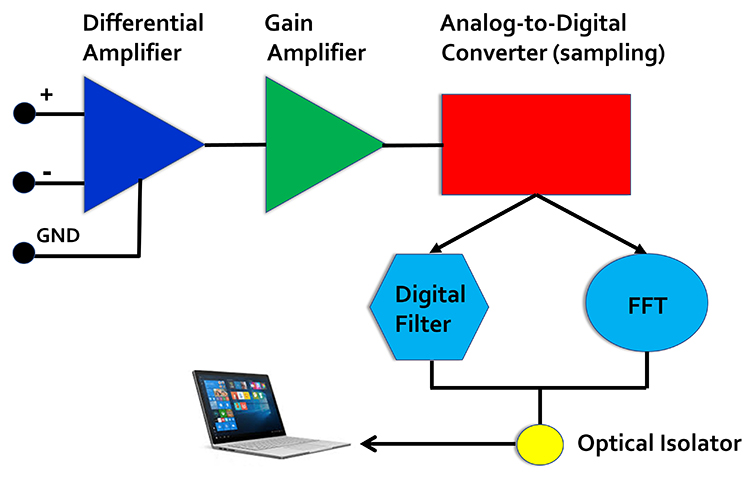

An electroencephalograph consists of the following stages: differential amplifier, gain amplifier, analog-to-digital converter, digital and FFT filters, and optical isolator.

Signal Amplification

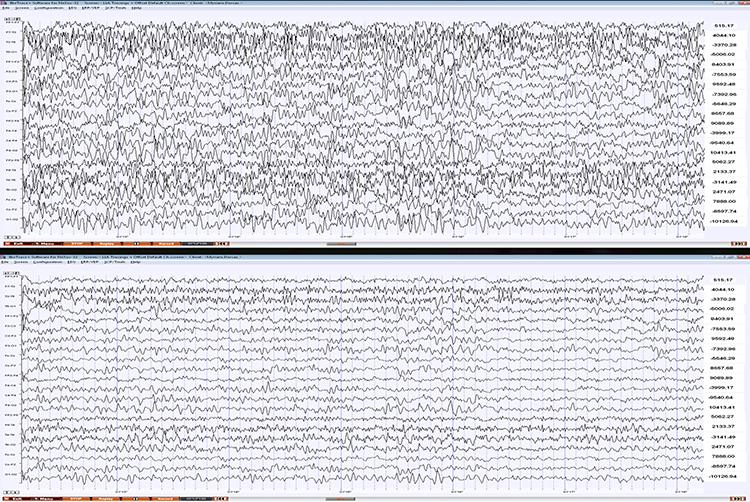

The biological signals monitored in biofeedback are very weak. The EEG signal, for example, is measured in microvolts (millionths of a volt). These signals must first be amplified over several stages to isolate the signal we are interested in and then drive displays. Stereo amplifiers perform the same tasks when they boost audio signals above the noise floor to levels that can power loudspeakers.Amplifiers share the properties of input sensitivity and gain. Input sensitivity is the maximum voltage level an amplifier can accept without producing clipping and distortion. The graphic below shows the same EEG signal with different sensitivity. The top tracing shows greater sensitivity than the bottom tracing, as evidenced by its substantially greater voltage swings.

Gain is an amplifier's ability to increase the magnitude of an input signal to create a higher output voltage. Gain is the ratio of output/input and is different for AC and DC systems. An amplifier that produces a 1-mV output from a 1-μV input has a gain of 1,000.

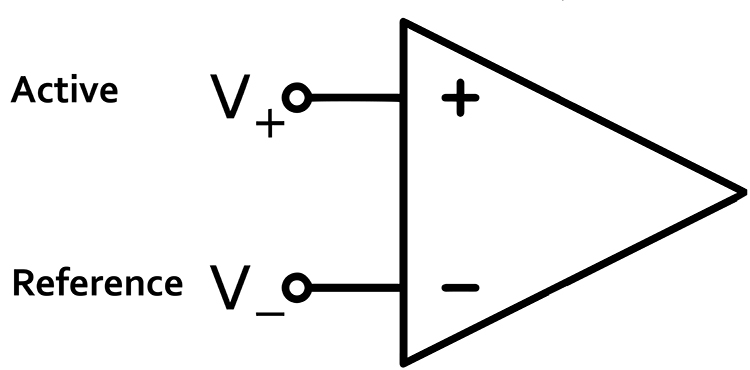

Differential Amplifiers

The EEG signal is first boosted by a differential amplifier and then by a gain amplifier. A differential amplifier, also called a balanced amplifier, amplifies the difference between the two inputs: the active (input 1) and reference (input 2). In the diagram below, the triangle represents the amplifier and the black circle the output voltage. Graphic © Hand Robot/Shutterstock.com.

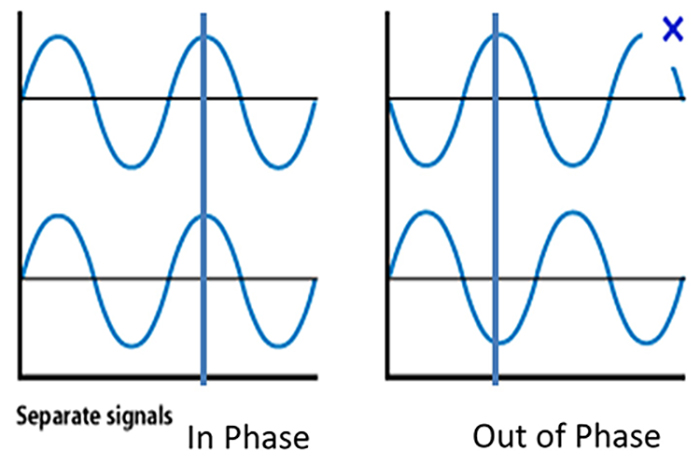

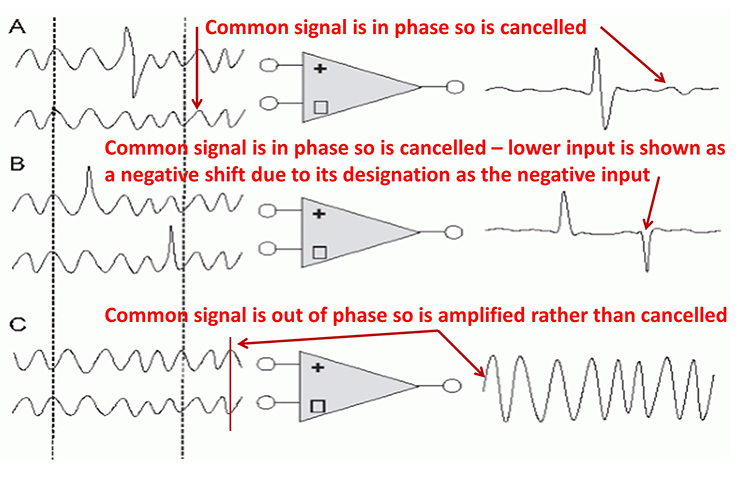

A differential amplifier combines two (or more) identical single-ended amplifiers with balanced inputs. The inputs are referenced to a common ground so that the resulting signals can be compared. The amplifiers are 180o out of phase so that signals that differ in frequency, amplitude, and phase are amplified. Only signal components that differ between two inputs are retained and amplified as output. Signals that are out of phase or possess different amplitudes are "seen" by the common-mode rejection process as different and are retained.

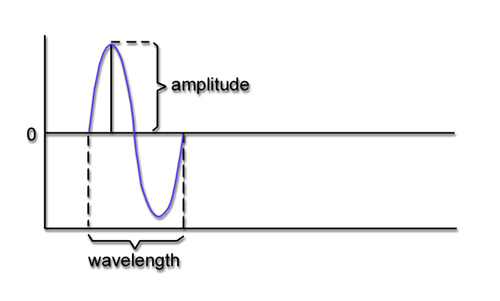

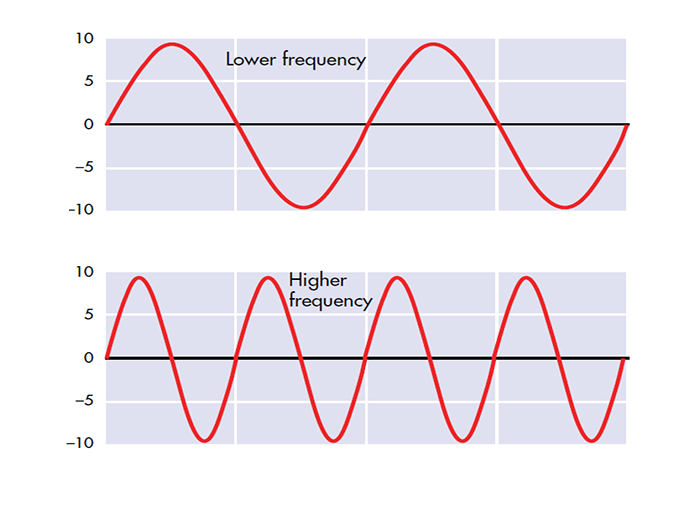

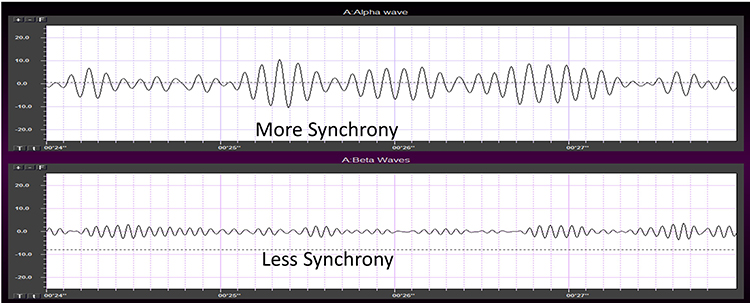

Frequency is the number of cycles per second (Hz).

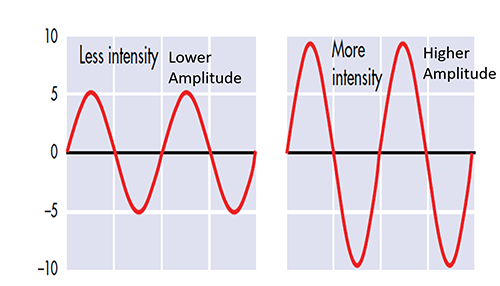

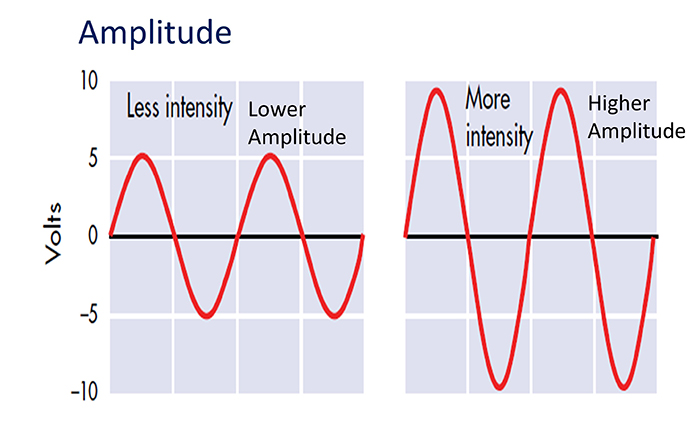

Amplitude is the signal voltage or power and is measured in microvolts or picowatts.

Phase is the similarity in timing of the waves at two locations. Note in the plot on the right. The two signals are 180o out of phase so that the top signal peaks when the bottom signal reaches its trough.

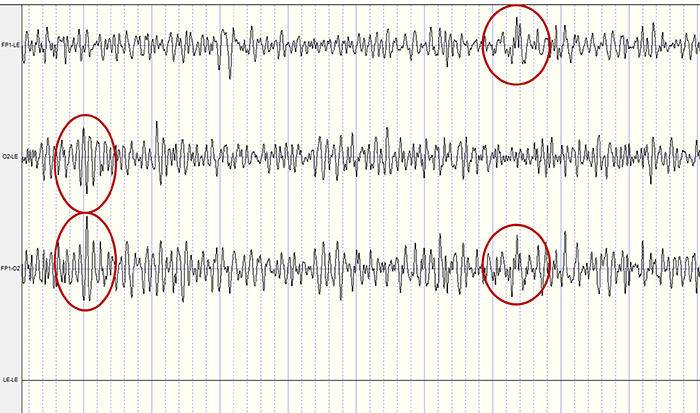

In the recording below, note the red-circled similar signals from the Fp1-LE and Fp1-O2 leads and the O2-LE and Fp1-O2 leads that should be subtracted by common-mode rejection. LE stands for the linked ear. LE-LE shows no voltage due to the complete subtraction of identical voltages from the exact anatomical location.

How does this reduce artifact? When there is no EEG activity, identical noise signals reach each amplifier. The differential amplifier subtracts these signals, canceling out the artifact. The output of a perfect differential amplifier would be 0.

The Challenges of Recording Infra-Slow EEG Activity

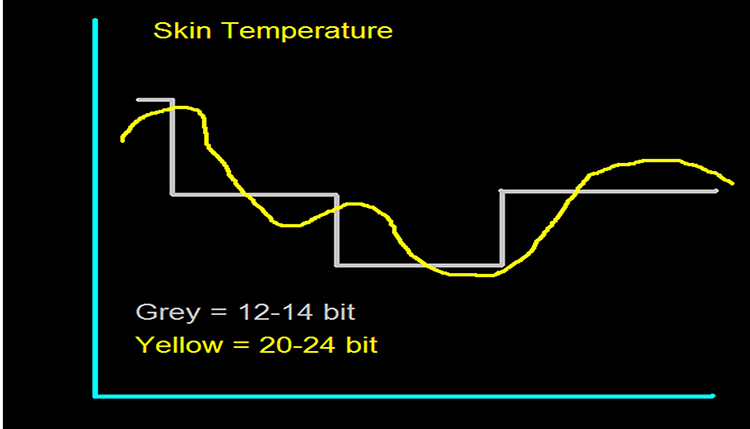

An AC amplifier has severe limitations when recording infra-slow (0-1 Hz) EEG activity. AC amplifiers exacerbate artifact effects. Client movement, eye movement, sweat, and transient field artifacts produce significant voltage changes. Long time constants over 80 s are recommended to integrate artifact-induced voltages over 2-4-min periods. However, persistent artifacts like eye movement will consistently degrade the signal-to-noise ratio of client feedback.Infra-slow recording requires DC-coupled amplifiers with a large dynamic range produced by 24-bit A/D converters to prevent saturation by slow drifts in baseline voltage. Standard EEG electrodes made of gold, steel, or tin are unacceptable because they suffer capacitance or energy storage, blocking lower frequencies. Silver/silver-chloride electrodes are ideal because they are reversible and do not polarize.

The clinician must distinguish slow artifacts from infra-slow signals. Eccrine sweat glands produce standing millivolt-range potentials. While these can be eliminated by partial skin puncturing, this practice risks infection transmission. Clinicians can identify eye blink and eye movement artifacts by their characteristic location. Body tilt, cough and strain, hyperventilation, and tongue movements produce high amplitude diffuse very slow potentials (Miller et al., 2007).

Common-Mode Rejection

A differential amplifier’s separation of signal from artifacts is measured by the common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR). Since these amplifiers cancel out noise imperfectly, signal and noise will be boosted. The CMRR specification compares the degree by which a differential amplifier boosts signal (differential gain) and artifact (common-mode gain). CMRR = differential gain/common-mode gain.CMRR should be measured at 50/60Hz where the strongest artifacts, like power line (50/60Hz) noise, are found. The smallest acceptable ratio is 100 dB (100,000:1), which means that signal is boosted 100,000 times more than competing noise. State-of-the-art equipment exceeds a 180-dB ratio. Lower ratios could result in unacceptable contamination of biological signals.

The graphic shows common-mode rejection when the common signal is in phase and out of phase.

You can take nine steps to maximize common-mode rejection:

(1) ensure that skin-electrode impedances are balanced within 1-3 Kohm. If both actives receive identical noise signals, the imbalance will make the signals look different and prevent complete subtraction of noise.

(2) active electrodes should be equidistant from the artifact source.

(3) active, reference, and ground sensors should be the same distance from each other.

(4) when using two or more channels, the ground and each active should be the same distance apart.

(5) ensure that there is a good ground connection. A deficient ground connection can make different voltages appear identical, defeating common-mode rejection.

(6) identify artifact sources. You can use a portable electroencephalograph or electromyograph like a Geiger counter. Move the unit around the room with EEG sensors connected but held in your hand. Artifact sources should produce the largest display values.

(7) remove the artifact sources you find. For example, fluorescent lights can be replaced with fixtures that produce less 50/60Hz noise.

(8) remove unused sensor cables from the encoder to not function as an antenna for 50/60Hz artifact.

(9) position the electroencephalograph and electrode cable to reduce artifact reception. Use the location and angle that yield the lowest readings when not attached to a patient (Thompson & Thompson, 2015).

The Effect of Electrode Location on Common Mode Rejection

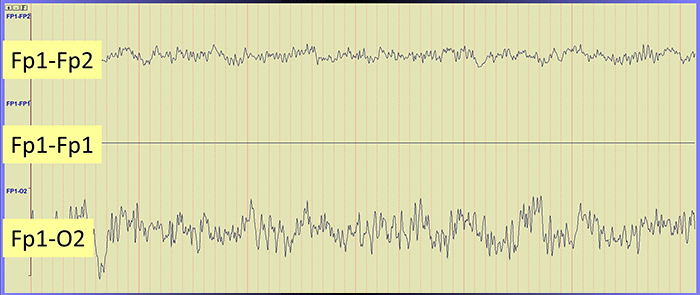

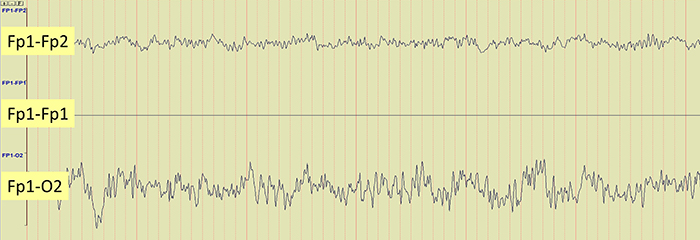

Brain activity is more similar when electrodes are close together and less similar when they are farther apart. This means that a differential amplifier may reject actual EEG voltages detected by adjacent electrodes. The sensors were placed at the same anatomical location (Fp1-Fp1) for maximum cancellation, as shown by the flat line in the recording below.

Differential Input Impedance

An amplifier’s differential input impedance further reduces the effect of unequal impedances. As EEG signals enter the amplifier, they are dropped across a network of resistors, presenting a differential input impedance in the Gohm (billion ohms) range. State-of-the-art instruments now exceed 10 Gohms. The differential input impedance must be at least 100 times skin-electrode impedance so that 99% or more of the signal can reach the electroencephalograph.Why is this important? Stronger signals help an amplifier differentiate EEG activity from noise, producing more accurate feedback.

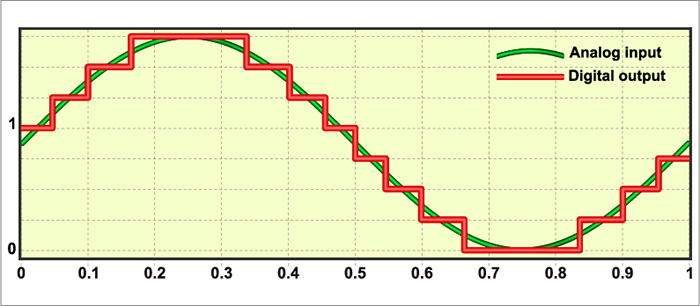

Sampling the EEG Signal

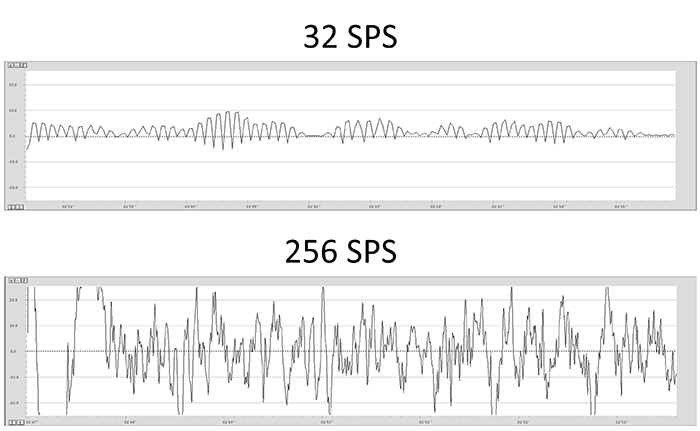

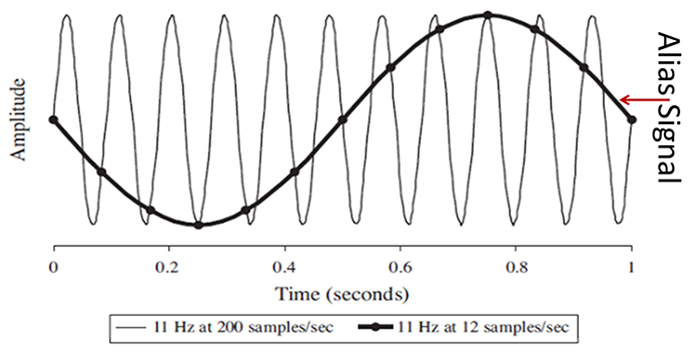

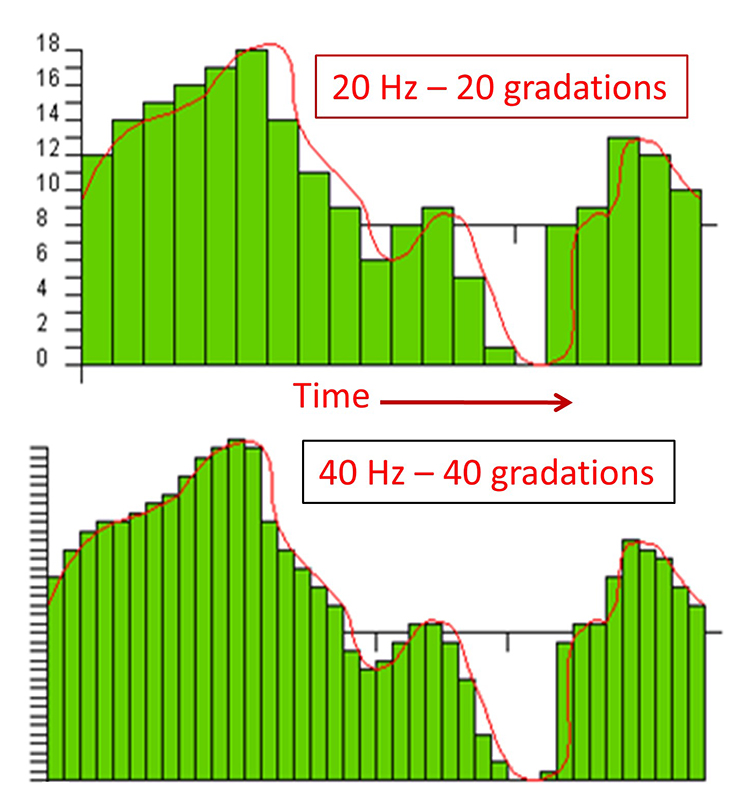

An analog-to-digital (A/D) converter samples the EEG signal at a fixed sampling interval. The sampling rate is the number of measurements taken within a given period. The sampling rate must be high enough to represent the signal being measured accurately.According to the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, an A/D converter's sampling rate should be at least twice the highest frequency component you intend to sample.

The American Clinical Neurophysiology Society (ACNS) guidelines recommend a minimum sampling rate of at least three times the high-frequency filter setting for digitization. This means at least 100 samples per second (sps) for a 35-Hz high-pass filter and at least 200 sps for a 70-Hz high-pass filter (Halford et al., 2016).

A sampling rate of 128 sps is acceptable for visual inspection of the EEG. A rate of 256 sps is typical, and rates from 500-1000 sps are preferred. The graphic below shows the same EEG signal sampled at 32 and 256 sps. The vertical scale (signal amplitude) is identical for both rates.

Sampling at rates that are too slow results in aliasing where an analog signal seems to have a lower frequency than it does. In the graphic below © Johns Hopkins University Press, "phantom" slow activity results from too few samples per second. An 11-Hz signal is sampled at 12 and 200 sps. The 12-sps rate produces an aliasing signal shown in black.

Resolution Depends on Bit Depth

An A/D converter's resolution is limited by the smallest signal amplitude it can sample. A bit number is the number of voltage levels that an A/D converter can discern. ACNS (Halford et al., 2016) recommends a 16-bit resolution, which can discriminate among 65,536 voltage levels and achieve 0.05-μV resolution. Lower A/D converter resolutions overemphasize small voltage increases.Signal Properties

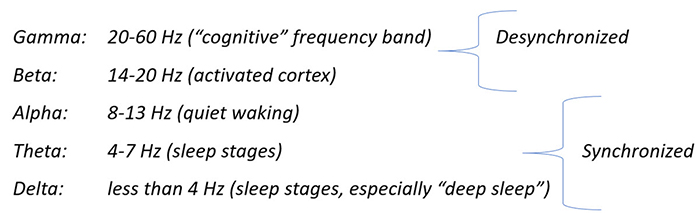

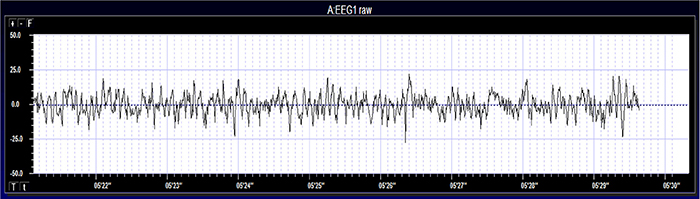

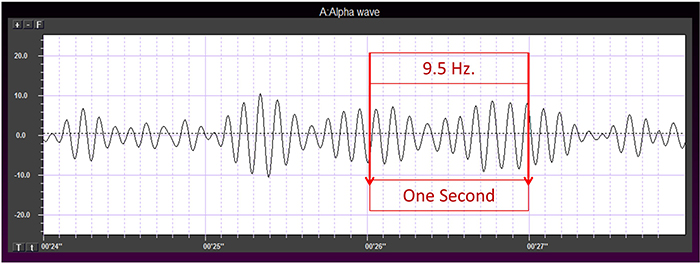

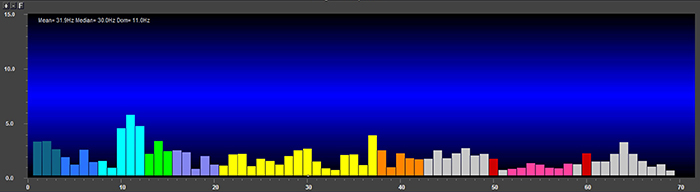

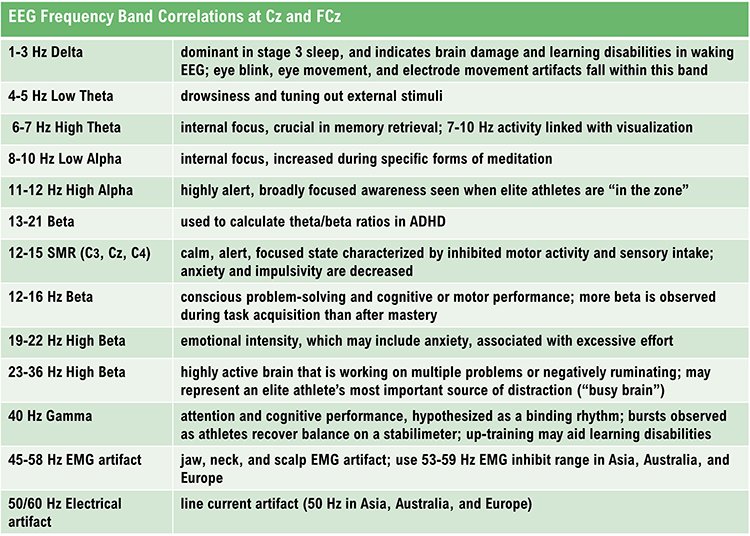

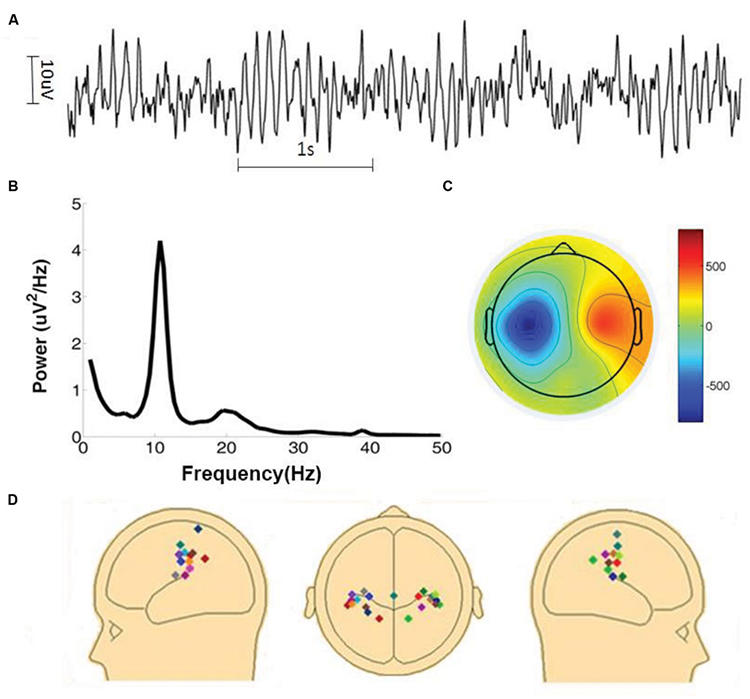

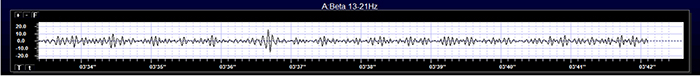

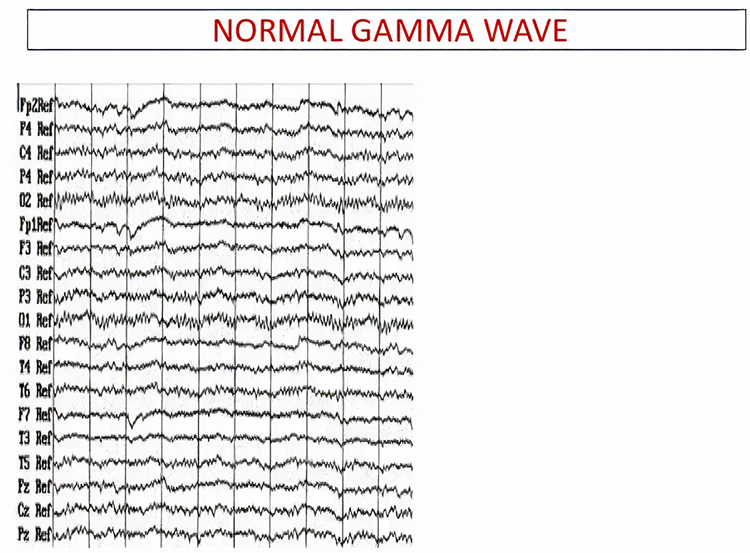

EEG signals may be described by their frequency and amplitude. A/D conversion utilizes digital filters to break the EEG into its component frequencies.

The movie below is a 19-channel BioTrace+ /NeXus-32 display of EEG activity from 1-64 Hz activity broken into component delta, theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands by digital filters © John S. Anderson.

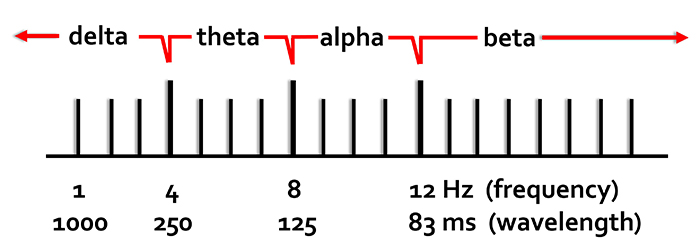

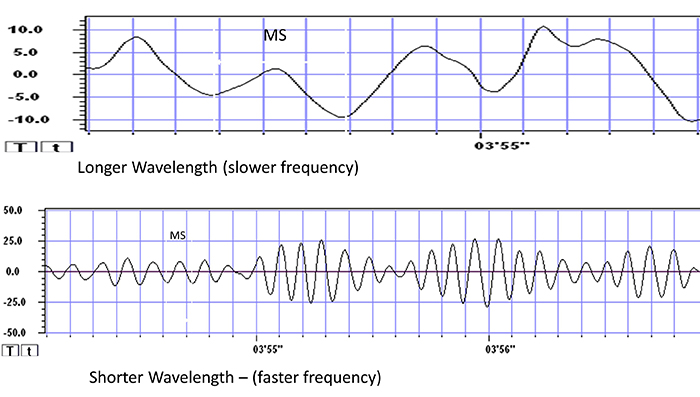

Recall that frequency is the number of cycles completed each second (Hz). The longer the wavelength, the slower the frequency. The delta, theta, alpha, and beta bands can be defined by wave frequency and wavelength, as shown in this graphic.

The next graphic illustrates the inverse relationship between wavelength and frequency. The time scale on the horizontal axis is in milliseconds. The amplitude scales are different for the upper (-10 to 10 μV) and lower (-50 to +50 μV) tracings.

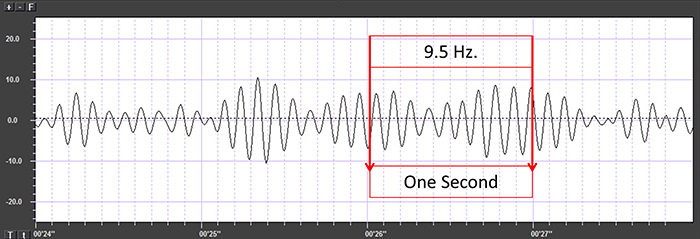

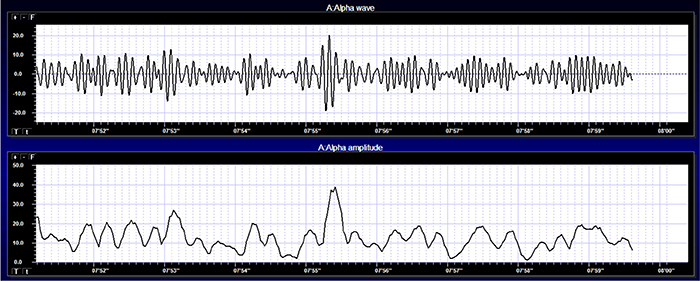

The graphic below shows a 9.5-Hz alpha wave. There are 9.5 peaks during a second.

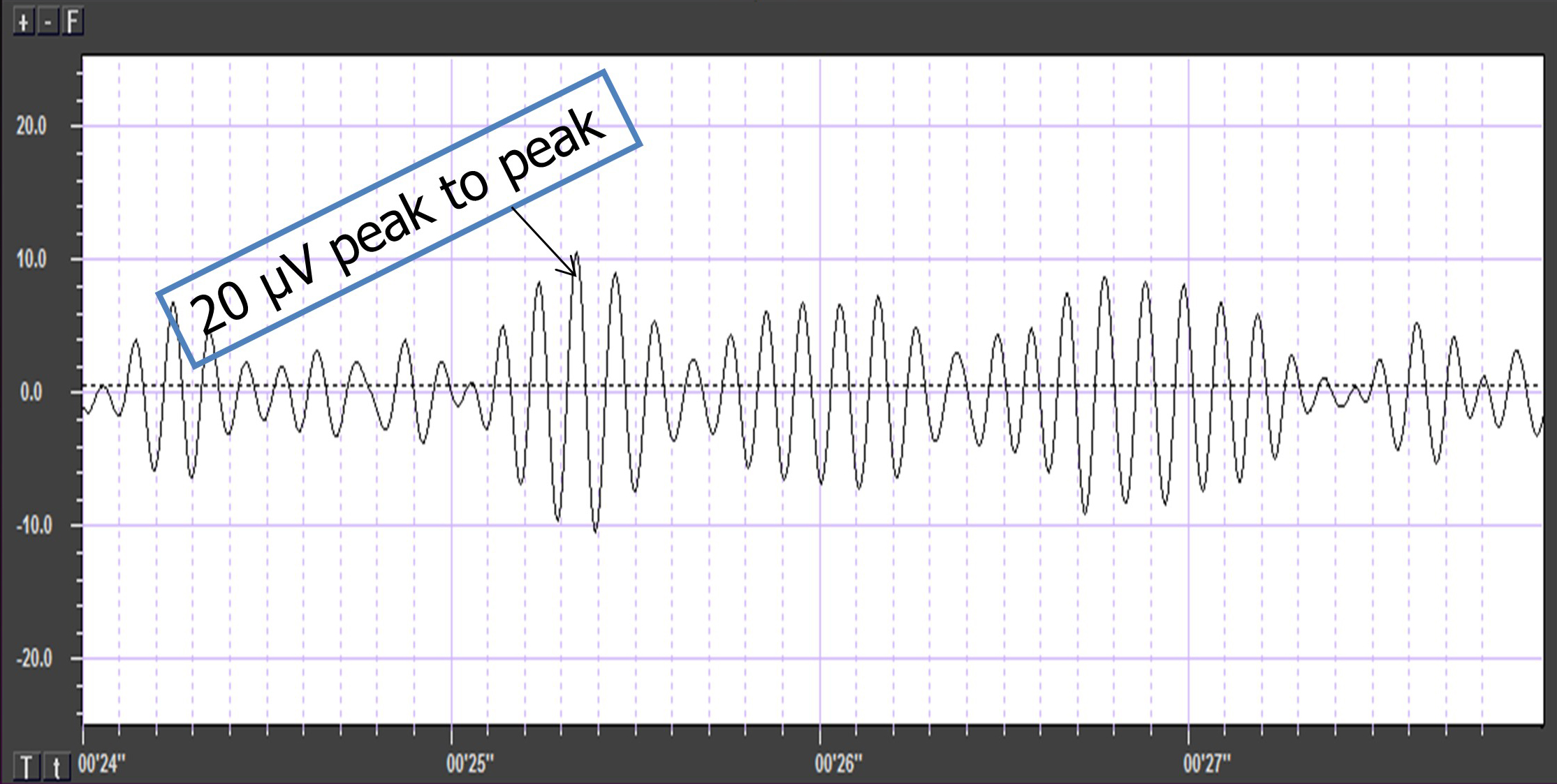

Also, recall that amplitude is signal voltage or power and is measured in microvolts or picowatts. The alpha wave below has a 20-μV amplitude.

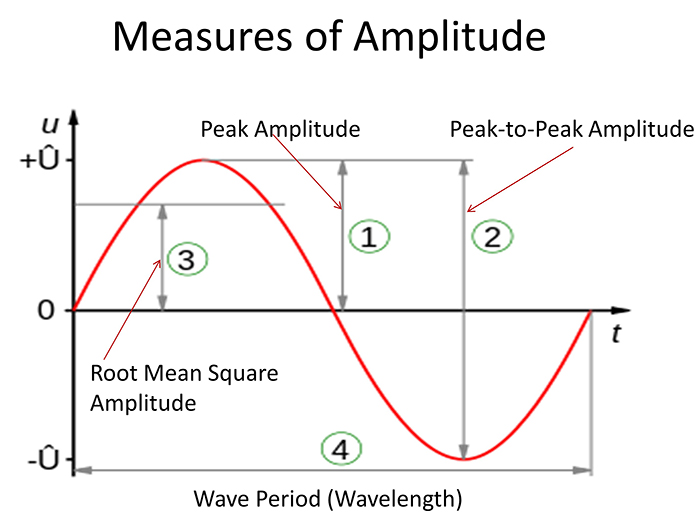

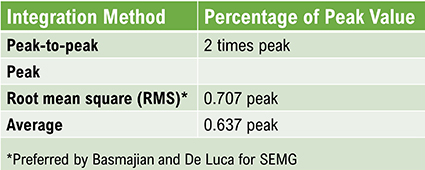

The EEG signal is sent to an integrator to measure signal amplitude in microvolts (μV) or picowatts. Integrators use four methods to calculate the voltage. The peak-to-peak method provides the largest estimate, equivalent to the energy contained between the positive and negative maximum values of the original AC waveform, which is 2 times the peak value. Peak voltage is 0.5 of the peak-to-peak value. Root mean square (RMS) voltage is 0.707 of the peak value and 20% higher than the average voltage. Average voltage is 0.637 of the peak value. The graphic below illustrates the peak, peak-to-peak, and root mean square integration methods.

Conversion among these methods is straightforward. If the peak-to-peak voltage is 20 μV, peak voltage is 10 μV, root mean square voltage is 7.07 μV, and average voltage is 6.37 μV.

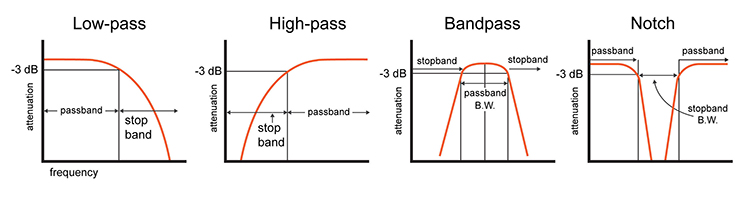

EEG Filters Define the Signal

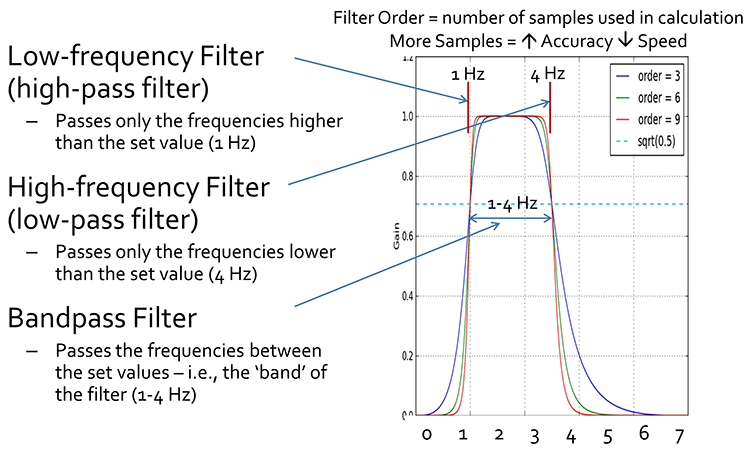

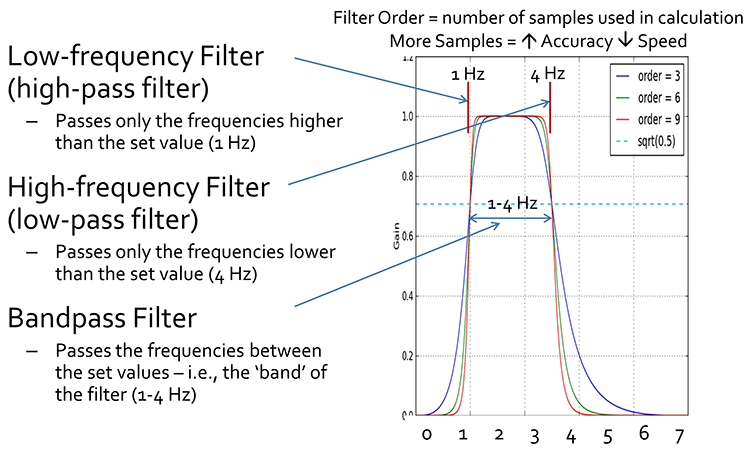

EEG filters select signals of interest and minimize artifacts. In this section, we will review high-pass, low-pass, bandpass, and notch filters. In the graphic below, the range of frequencies passed through a filter is called the passband, and the range that is sharply attenuated is called the stopband.

A high-pass filter only passes frequencies higher than a set value (e.g., 1 Hz). A low-pass filter only passes frequencies lower than a specified value (e.g., 40 Hz). A bandpass filter passes frequencies between the set values, the "band" of the filter (e.g., 1-40 Hz).

10-Hz Low-Pass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 10-Hz low-pass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

20-Hz Low-Pass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 20-Hz low-pass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

30-Hz Low-Pass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 30-Hz low-pass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

40-Hz Low-Pass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 40-Hz low-pass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

10-Hz High-Pass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 10-Hz high-pass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

20-Hz High-Pass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 20-Hz high-pass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

30-Hz High-Pass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 30-Hz high-pass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

Bandpass Filters

1-40-Hz Bandpass Filter

The movie below shows the output of a 1-40-Hz bandpass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

8-12-Hz Bandpass Filter

The movie below shows the output of an 8-12-Hz bandpass filter with a vertical scale of 0-50 μV © John S. Anderson.

The movie below shows the output of three bandpass filters for delta, theta, and alpha © John S. Anderson.

The movie below generously provided by John S. Anderson shows a "raw" or "wave" display of oscillating electrical information using a positive/negative scale with 0.0 in the middle with the voltage displayed as peak-to-peak μV.

The movie © John S. Anderson shows the same alpha waveform plotted along two scales. The top display plots the waveform on a scale that ranges from -20 to +20 μV. The bottom "amplitude" display plots the voltage on a scale that ranges from 0- 50 μV where all values are positive.

The movie © John S. Anderson shows the conversion of the complex EEG signal into its spectral components.

The movie © John S. Anderson shows the spectrum magnitude (average amplitude over a given time) in the top display and power (μV2) in the bottom display.

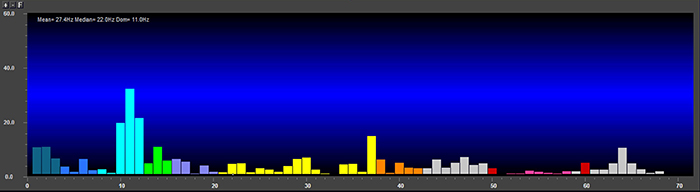

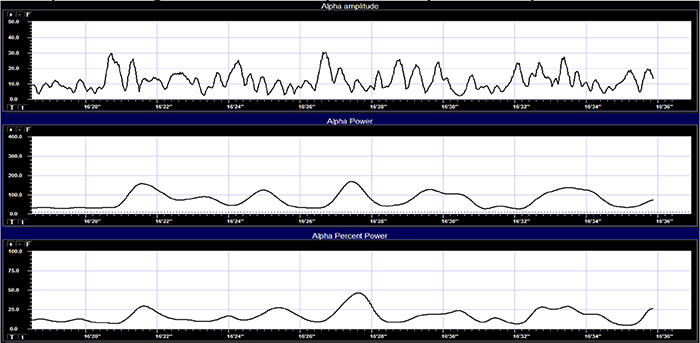

The movie © John S. Anderson shows the same alpha activity displayed in terms of amplitude (positive voltages), power or amplitude2 (picowatts/resistance), and percent power (signal power as a percentage of total EEG power from 0-100%).

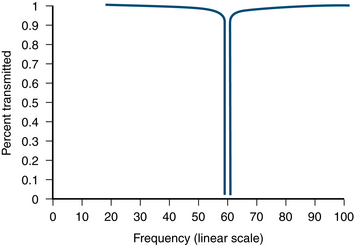

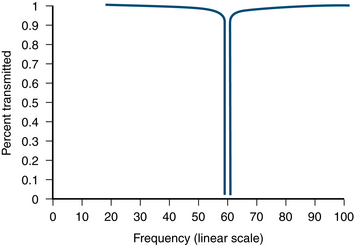

Notch Filter

A notch filter suppresses a narrow band of frequencies produced by line current (e.g., 50/60Hz artifact), as shown below by a graphic by Neupsy Key. Use notch filters as a last resort.

The narrated video below © John S. Anderson displays the same 21-channel recording viewed using different montages with a 60-Hz notch filter on and off.

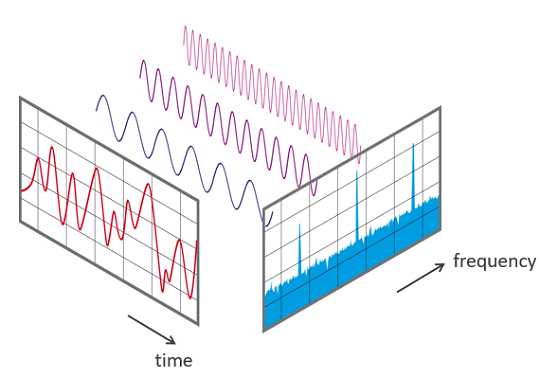

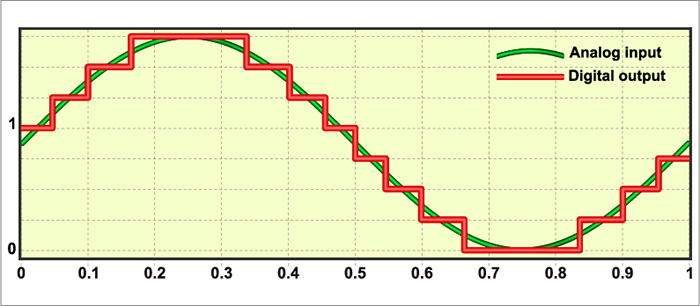

Digital Filters

Digital filters use digital processors, like a digital signal processing (DSP) chip, to exclude unwanted frequencies. First, an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) samples and digitizes the analog signal, representing signal voltages as binary numbers. Second, a DSP chip performs calculations on the binary numbers. Third, a digital-to-analog converter (DAC) may transform the sampled, digitally-filtered signal back to analog form.Three main methods of digital filtering are Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT), finite impulse response (FIR), and infinite impulse response (IIR).

FFT filters convert the EEG signal into a set of sine waves that vary in frequency, amplitude, and phase.

FIR filters have a finite-duration impulse response and calculate a moving weighted average of digitally-sampled voltages.

IIR filters have an infinite impulse response and employ feedback to calculate a moving weighted average of digitally-sampled voltages.

FFT, FIR, and IIR methods enjoy four advantages over analog filters. First, a clinician can retrospectively adjust the filter settings as they review the EEG record since digital filters are programmable. Second, digital filters can be designed to minimize phase distortion (displacement of the EEG waveform in time). Third, digital filters are stable over time and across a range of temperatures. Fourth, digital filters accurately process low-frequency signals. Graphic © Fouad A. Saad/Shutterstock.com shows the digital reconstruction of an analog waveform.

Since these three digital filtering methods can yield different statistical values, they cannot be used interchangeably. Only compare FFT statistics with themselves and not FIR or IIR statistics (Thompson & Thompson, 2016).

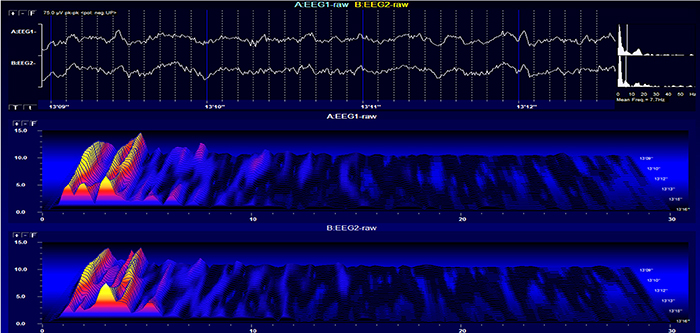

Below is a BioGraph ® Infiniti EEG three-dimensional FFT display. Frequency is displayed on the X-axis, amplitude on the Y-axis, and time on the Z-axis.

Safety Precautions

Like computer-based data acquisition systems, line-powered equipment can expose both a client and practitioner to shock hazards. Both should avoid contact with metal surfaces, and water spills should be immediately cleaned up. Graphic © DenisNata/Shutterstock.com.

Exposure to Current Can Injure and Cause Death

A 1-second exposure to a current exceeding 5 mA can injure. An 18-mA current can affect breathing. A 50-mA current can cause fatal ventricular fibrillation in which the heart chambers cannot pump blood (Peek, 2016). Animation © 2010 Scholarpedia.

Biomedical engineers prevent shock hazards through ground fault interrupt circuits, optical isolation, fiber optic connections, and telemetry. Graphic © Sergey Nivens/Shutterstock.com.

Ground Fault Interrupt Circuit

A ground fault interrupt circuit is designed into some power outlets to shut down power when a short circuit occurs. This protective circuit monitors current leakage. When harmful leakage is detected (> 5 mA), it triggers a circuit breaker that shuts off power to the equipment, protecting the client, therapist, and hardware.Montgomery (2004) recommended plugging the entire biofeedback system into the same power outlet to create a common ground so that current leakage in any of your equipment will trigger the ground fault interrupt circuit.

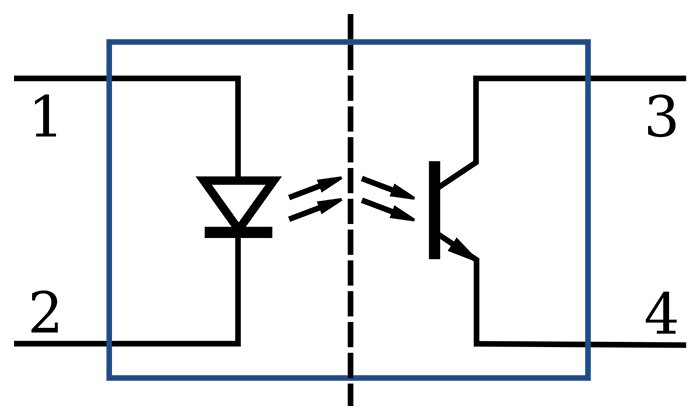

Optical Isolation

Optical isolation protects a client from hardware receiving AC power. An optical isolator (opto-isolator) converts a biological signal into a beam of light using an LED source, the light crosses a dialectic barrier (insulation) located in the center (open circuit), and a phototransistor reconverts the light into an electrical signal.

Fiber Optic Connections

Fiber optic connections, thin, flexible cables that transmit digital signals as pulses of light, transmit photons between the electrodes and data acquisition system. This prevents current from leaking from a computer to a client since electrons cannot travel through fiber optic cables. This approach also reduces contamination by electrical artifacts like power line noise.

Telemetry

Telemetry can wirelessly transmit physiological data from a battery-powered encoder unit to a computer many meters away. This technology protects clients from shock since current surges cannot travel across a Bluetooth connection (Montgomery, 2004).

Glossary

active electrode: the electrode that is placed over a site that is a known EEG generator like Cz.

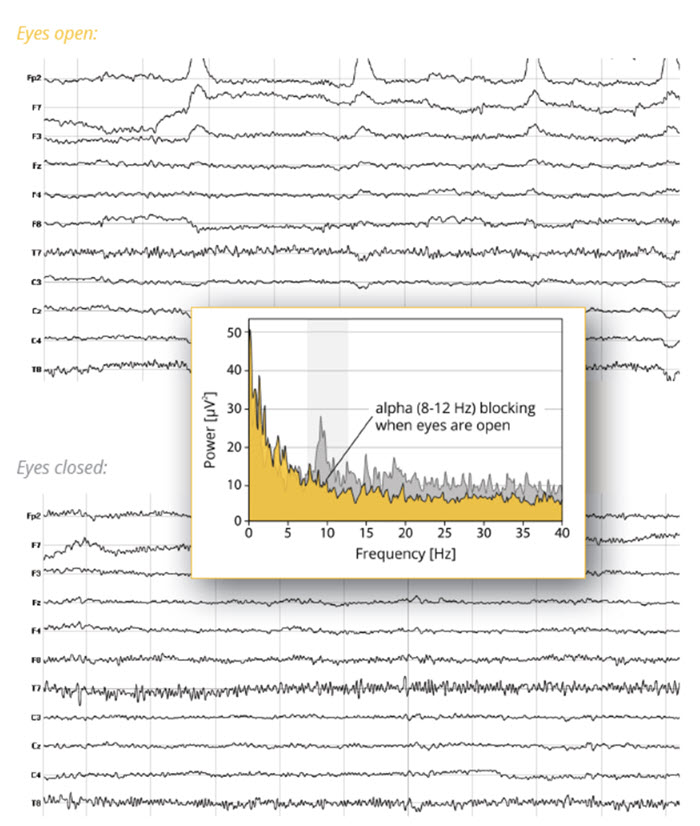

alpha blocking: the replacement of the alpha rhythm by low-amplitude desynchronized beta activity during movement, attention, mental effort like complex problem-solving, and visual processing.

alternating current (AC): an electric current that periodically reverses its direction.

ampere (A): the unit of electrical current or the flow rate of electrons through a conductor. One volt dropped across one ohm of resistance produces a current flow of one ampere.

amplitude: the strength of the EMG signal measured in microvolts or picowatts.

analog-to-digital converter (ADC): an electronic device that converts continuous signals to discrete digital values.

artifact: false signals like 50/60Hz noise produced by line current.

atom: the basic unit of matter consisting of a central nucleus that contains protons and neutrons and orbiting electrons.

atomic number: the number of protons in the nucleus of an atom that defines an element.

atomic weight: the approximate number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of an atom.

average voltage: 0.637 of the peak voltage.

bandpass filter: the filter that passes frequencies between the set values, the "band" of the filter (e.g., 1-40 Hz).

behavioral test (tracking test): a test of the entire signal chain (EEG sensor, differential amplifier, gain amplifier, cable, encoder, and computer) performance by asking a client to act and then observing the effects on the EEG.

bias potential: spurious voltage produced by the exchange of metal ions donated by the electrodes and electrolytes in the absence of a biological current.

bipolar recording: a recording method that uses two active electrodes and a common reference.

bit number: the number of voltage levels that an A/D converter can discern. A resolution of 16 bits means that the converter can discriminate among 65,536 voltage levels.

charge (Q): the imbalance between the number of positively and negatively charged particles in a given place or between two locations.

closed circuit: a complete path that allows electrons to travel from the power source, through the conductor and resistance, and back to the source.

common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR): the degree by which a differential amplifier boosts signal (differential gain) and artifact (common-mode gain).

conductance (G): the ability of a material like copper or silver to carry an electric current. Conductance is measured in siemens (formerly mhos).

conductor: a material that readily allows electron movement like a copper wire.

continuity test: a procedure to ensure that a circuit is closed. For example, a cable is not broken.

coulomb: approximately 6.24 x 1018 or 6 billion billion electrons.

current (I): the movement of electrons through a conductor measured in amperes (A).

DC offset: the voltage that results from combinations of factors including electrode and gel/paste materials, interactions with skin, environment (humidity and temperature), and sweat gland activity due to stress level.

differential amplifier (balanced amplifier): a device that boosts the difference between two inputs: the active (input 1) and reference (input 2).

differential input impedance: the opposition to an AC signal entering a differential amplifier as it is dropped across a resistor network.

digital filter: device that mathematically removes unwanted or extracts valuable aspects of a sampled, discrete-time signal.

direct current (DC): an electric current that flows in only one direction, as in a flashlight.

electrode: a specialized conductor that converts biological signals like the EEG into currents of electrons.

electromotive force (EMF): a difference in electrical potential that "pushes" electrons to move in a circuit.

electron: a negatively-charged particle that rotates around the nucleus at varying distances and participates in chemical reactions.

elements: substances that contain identical atoms and cannot be reduced by common chemical reactions.

energy level: one of an electron's possible orbits around a nucleus at a constant distance.

epidermis: the outermost skin layer.

fiber optic cable: a thin, flexible cable that transmits digital signals as pulses of light with the advantages of high-speed data transmission, electrical isolation, and resistance to electromagnetic interference.

finite impulse response (FIR) filter: filter with a finite-duration impulse response.

frequency (Hz): the number of complete cycles that an AC signal completes in a second, usually expressed in hertz.

gain: an amplifier's ability to increase the magnitude of an input signal to create a higher output voltage; the ratio of output/input voltages.

ground electrode: a sensor placed on an earlobe, mastoid bone, or the scalp that is grounded to the amplifier.

ground fault interrupt circuit: a protective device that opens a circuit—shutting down power—when current leakage exceeds 5 mA.

hertz (Hz): the unit of frequency measured in cycles per second.

high-pass filter: a filter that only passes frequencies higher than a set value (e.g., 1 Hz).

impedance (Z): complex opposition to an AC signal measured in Kohms.

impedance meter: device that uses an AC signal to measure impedance in an electric circuit, such as between active and reference electrodes.

impedance test: the automated or manual measurement of skin-electrode impedance.

infinite impulse response (IIR) filter: a filter with an infinite impulse response and employ feedback as they calculate a moving weighted average of digitally-sampled voltages.

input sensitivity: the maximum voltage level an amplifier can accept without producing clipping and distortion.

insulator: material that resists the flow of electricity like glass and rubber.

interstitial fluid: fluid between cells through which biological signals travel via volume conduction.

ion: an atom or molecule with a positive or negative electrical charge.

low-pass filter: a filter that only passes frequencies lower than a set value (e.g., 40 Hz).

mastoid bone (or process): bony prominence behind the ear.

mho: the unit of conductance replaced by the siemen.

microsiemen (μS): the unit of conductance that is one-millionth of a siemen.

microvolt (μV): the unit of amplitude (signal strength) that is one-millionth of a volt.

milliampere (mA): unit of electrical current that is one-thousandth of an ampere.

millivolt (mV): unit of amplitude (signal strength) that is one-thousandth of a volt.

monopolar recording: a recording method that uses one active and one reference electrode.

motor unit: an alpha motor neuron and the skeletal muscle fibers it innervates.

notch filter: a filter that suppresses a narrow band of frequencies, such as those produced by line current at 50/60Hz.

nucleus: central mass of an atom that contains protons and neutrons.

Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem: the perfect reconstruction of the analog signal requires sampling at two times its highest frequency. A signal whose highest frequency is 1000 Hz should be sampled 2000 times per second.

ohm (Ω): the unit of impedance or resistance.

Ohm's law: voltage (E) = current (I) X resistance (R). The “amount” of current (I) flowing through a conductor is equal to the voltage (E) or “push” divided by the resistance (R).

open circuit: an incomplete path that prevents electron movement from the power source, through the conductor, and back to the source. For example, a broken sensor cable.

optical isolation: a device that converts a biological signal into a beam of light, the light crosses a gap (open circuit), and a photoreceptor reconverts the light into an electrical signal.

passband: the range of frequencies that is passed through a filter.

peak voltage: 0.5 of the peak-to-peak voltage.

peak-to-peak voltage: the voltage contained between the positive and negative maximum values of the original AC waveform.

phase: the degree to which the peaks and valleys of two waveforms coincide.

phase distortion: the displacement of the EEG waveform in time.

picowatt: billionths of a watt.

polarization: chemical reactions produce separate regions of positive and negative charge where an electrode and electrolyte make contact, reducing ion exchange.

power (W): the rate at which energy is transferred, which is proportional to the product of current and voltage. Power is measured in watts.

proton: positively charged subatomic particle found in the nucleus of an atom.

Quantitative EEG (qEEG): digitized statistical brain mapping using at least a 19-channel montage to measure EEG amplitude within specific frequency bins.

reference electrode: the electrode placed over a less-electrically active site like the mastoid bone behind the ear.

resistance (R): the opposition to a DC signal by a resistor measured in ohms.

resistor: a component in electric circuits that resists current flow.

resolution: degree of detail in a biofeedback display (0.1 μV) or the number of voltage levels that an A/D converter can discriminate (16 bits or discrimination among 65,536 voltage levels).

root mean square (RMS) voltage: 0.707 of the peak voltage.

short circuit: a lower-resistance electrical circuit created by the unintended contact between components that accidentally diverts the current.

skin conductance level (SCL): a tonic measurement of how easily an AC or DC passes through the skin, expressed in microsiemens.

skin resistance level (SRL): a tonic (resting) measurement of the opposition to an AC or DC as it passes through the skin, expressed in Kohms.

stopband: the range of frequencies that is sharply attenuated by a filter.

superconductor: a material that conducts electricity without resistance.

telemetry: remote monitoring and transmission of information. An encoder measures physiological activity and transmits these data to a computer for analysis.

tracking test (behavioral test): a test of the entire signal chain (EEG sensor, differential amplifier, gain amplifier, cable, encoder, and computer) performance by asking a client to act and then observing the effects on the EEG.

transducer: device that transforms energy from one form to another. Electrodes convert ionic potentials into electrical potentials.

ventricular fibrillation: a medical emergency in which the lower heart chambers contract in a rapid and unsynchronized fashion and cannot pump blood.

volume conduction: the movement of biological signals through interstitial fluid.

volt (V): unit of electrical potential difference (electromotive force) that moves electrons in a circuit.

voltage (E): the amount of electrical potential difference (electromotive force).

voltohmmeter: a device that uses a DC signal to measure resistance in an electric circuit, such as between active and reference electrodes.

watt (W): a unit of power used to express signal strength in the qEEG.

REVIEW FLASHCARDS ON QUIZLET

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this module, explain why low-and-balanced skin-electrode impedances are important in neurofeedback training. Describe the precautions you take to achieve acceptable impedance values. How do you measure impedance with your neurofeedback system?

References

Andreassi, J. L. (2000). Psychophysiology: Human behavior and physiological response. Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc.

Basmajian, J. V. (Ed.). (1989). Biofeedback: Principles and practice for clinicians. Williams & Wilkins.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Tassinary, L. G. (Eds.). (1990). Principles of psychophysiology. Cambridge University Press.

Collura, T. F. (2014). Technical foundations of neurofeedback. Taylor & Francis.

Demos, J. N. (2005). Getting started with neurofeedback. W. W. Norton & Company.

Fisch, B. J. (1999). Fisch and Spehlmann's EEG primer (3rd ed.). Elsevier.

Floyd, T. L. (1987). Electronics fundamentals: Circuits, devices, and applications. Merrill Publishing Company.

Grant, A. (2015). Four elements earn permanent seats on the periodic table. Science News.

Halford, J. J., Sabau, D., Drislane, F. W., Tsuchida, T. N., & Sinha, S. R. (2016). American Clinical Society Guideline 4: Recording clinical EEG on digital media. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 33(4), 317-319. https://doi.org/10.1080/21646821.2016.1245563

Hughes, J. R. (1994). EEG in clinical practice (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Kubala, T. (2009). Electricity 1: Devices, circuits, and materials (9th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Libenson, M. H. (2010). Practical approach to electroencephalography. Saunders Elsevier.

Miller, J. W., Kim, W. S., Homes, M. D., & Vanhatalo, S. (2007). Ictal localization by source analysis of infraslow activity in DC-coupled scalp EEG recordings. NeuroImage, 35(2), 583-597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.018

Montgomery, D. (2004). Introduction to biofeedback. Module 3: Psychophysiological recording. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Nilsson, J. W., & Riedel, S. A. (2008). Electric circuits (8th ed.). Pearson Prentice-Hall.

Peek, C. J. (2016). A primer of traditional biofeedback instrumentation. In M. S. Schwartz, & F. Andrasik (Eds.). (2016). Biofeedback: A practitioner's guide (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

Stern, R. M., Ray, W. J., & Quigley, K. S. (2001). Psychophysiological recording (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). The biofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Wadman, W. J., & Lopes da Silva, F. H. (2011). In D. L. Schomer & F. H. Lopes da Silva (Eds.). Niedermeyer's electroencephalography: Basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields (6th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

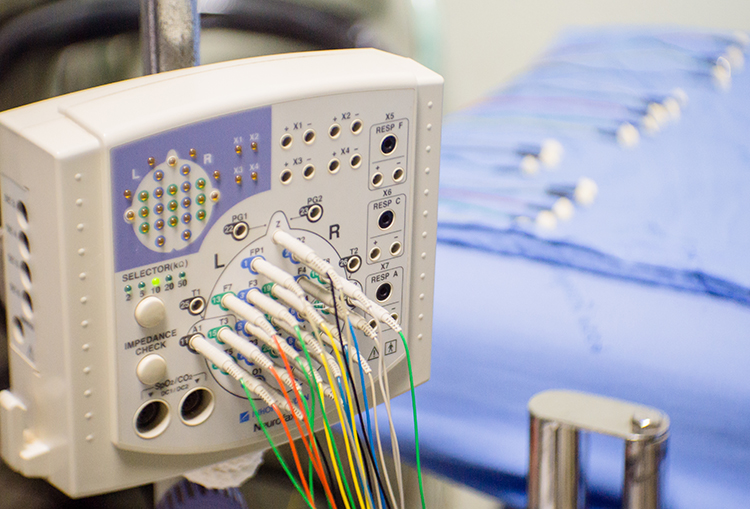

B. SIGNAL ACQUISITION

Clinicians monitor EEG activity using the classical International 10-20 System for standardized electrode placement or the modified "10-10" system known as the Modified Combinatorial Nomenclature System. They often record from several sites and measure the amplitude of EEG signals within frequency bands (like alpha and theta) to provide a complete picture of brain activity. Software-based montage reformatting allows clinicians to reanalyze session data by referencing an electrode to other sites or combinations of sites. This system also allows for the computation of multiple variables associated with communication and network functions within the central nervous system (CNS)

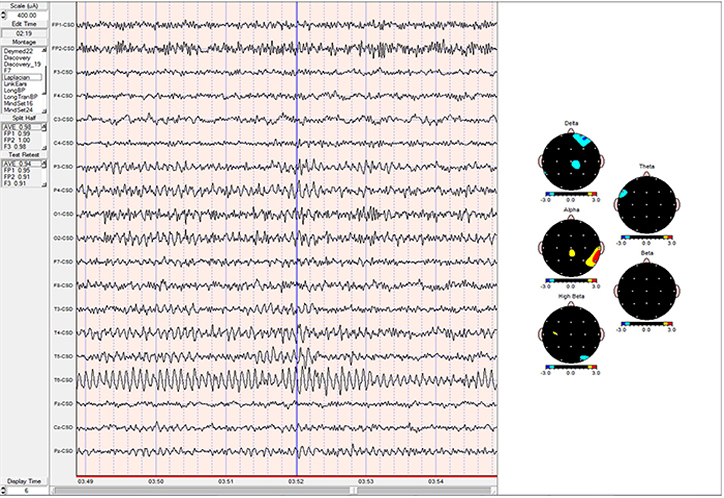

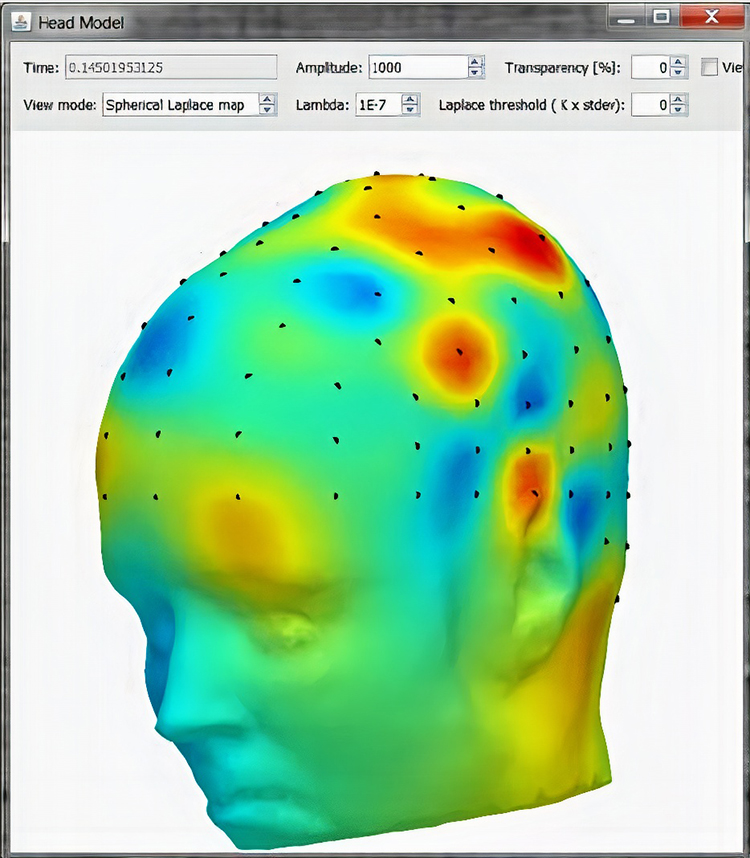

The Quantitative EEG (qEEG) measures EEG amplitudes within selected frequency bands. A full-cap 21-channel EEG recording (19 scalp sensors plus two "reference" sensors) and resulting qEEG analysis may be valuable in designing treatment protocols for complicated cases like Asperger's or traumatic brain injury. EEG topography displays the qEEG on a cortical surface map to show the spatial distribution of EEG activity.

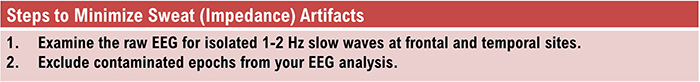

Contamination of the EEG by physiological and exogeneous artifacts requires that clinicians take extensive precautions, examine the raw EEG record, and remove contaminated epochs through artifacting. Impedance tests and behavioral tests help ensure the fidelity of EEG recording.

Finally, clinicians interpret EEG recordings with an understanding of normal values and recognition of the effects of eye closure, age, diurnal influences, alertness and drowsiness, medication, and relaxation on these readings. Graphic © Medical-R/Shutterstock.com.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses III. Instrumentation and Electronics - B. Signal Acquisition.

This unit covers International 10-20 and 10-10 Systems, Comparison of Neuroimaging Techniques, Using a Limited Number of Electrodes, Montage Options and Their Consequences, Recognizing and Correcting Signals of Noncerebral Origin, and Recognizing Normal EEG Patterns.

International 10-20 and 10-10 Systems

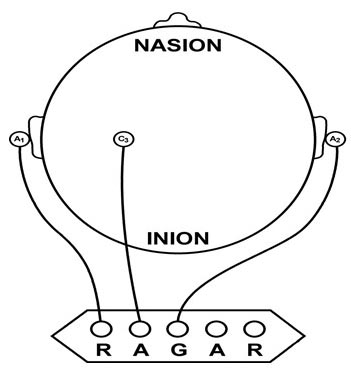

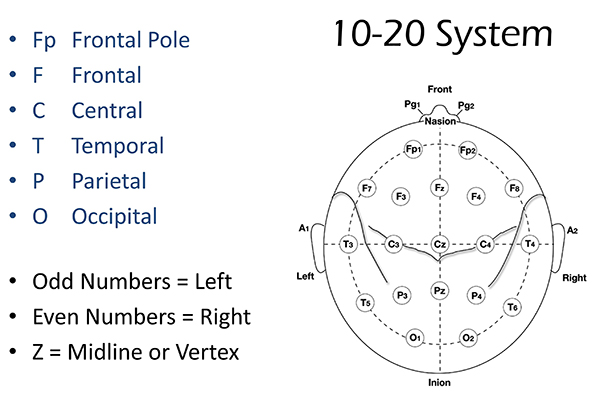

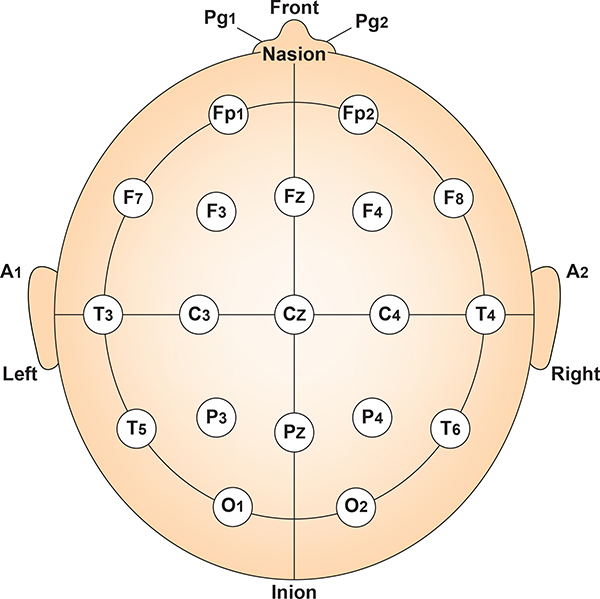

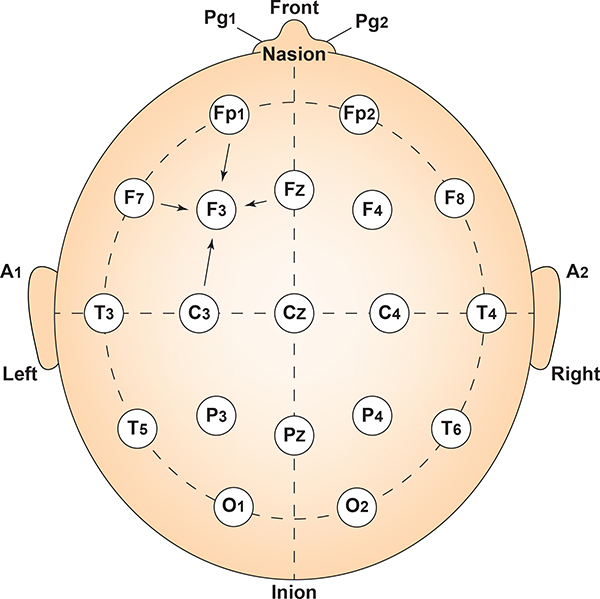

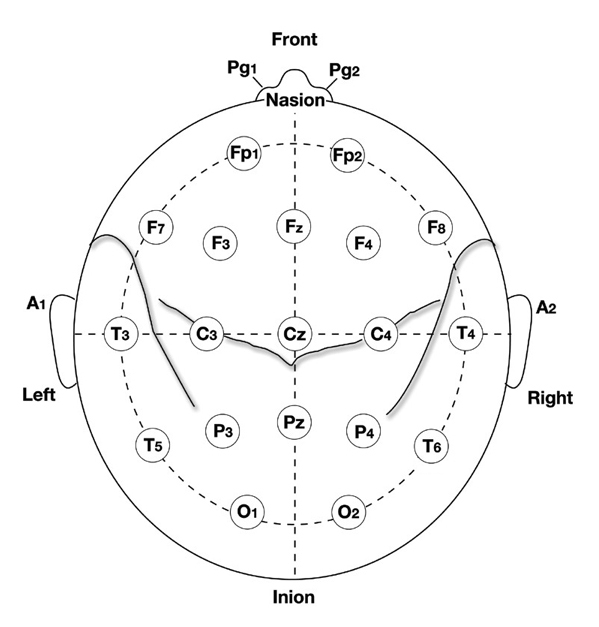

The International 10-20 system is a standardized procedure for electrode placement on 19 scalp and reference and ground sites. Electrodes measure electrical activity from a surrounding area the size of a quarter. The site recorded may be distant from the EEG generator due to neural pathways.

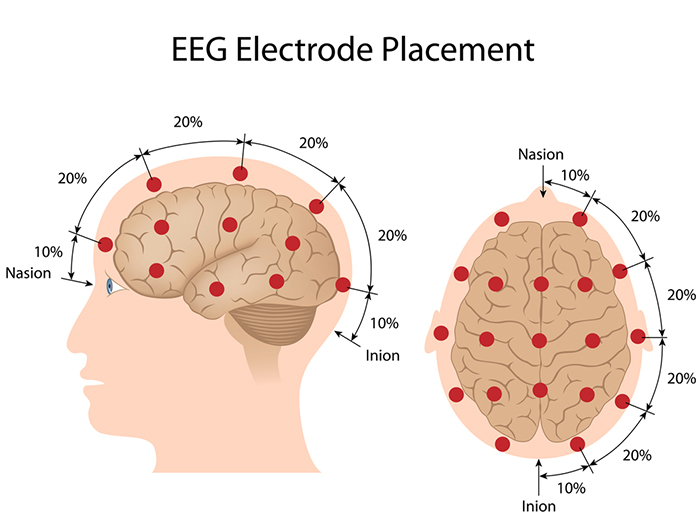

The International 10-20 system calculates the distance from the nasion to the inion and from the left preauricular notch to the right preauricular notch. The 19 active electrode positions are found taking either 10% or 20% of these distances. Check out the YouTube video The International 10-20 System. Four essential landmarks are the nasion, inion, preauricular points, and vertex. Graphic © Alila Medical Media/Shutterstock.com.

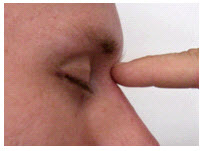

The nasion is the depression at the bridge of the nose.

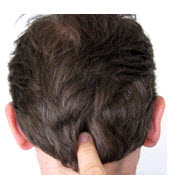

The inion is the bony prominence on the back of the skull in the middle of the inion ridge.

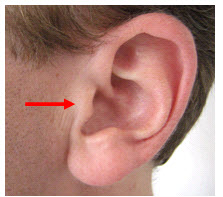

The left and right preauricular points are slight depressions located in front of the ears and above the earlobe. The flap at the opening of the ear is called the tragus.

The vertex (Cz) is the intersection of imaginary lines drawn from the nasion to inion and between the two preauricular points. Cz is 50% of the total distance between the nasion and inion and 50% of the total distance between the two preauricular points. Minaanandag adapted the diagram below from Fisch (1999).

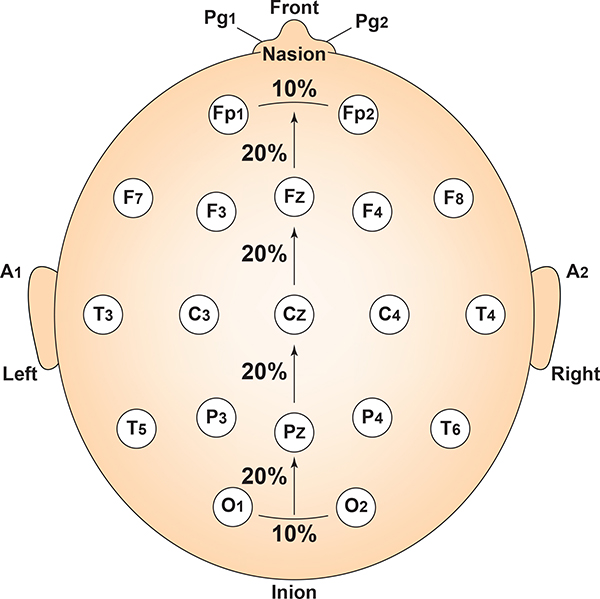

The 10-20 system received its name because electrode sites are separated by 10% or 20% of the distance between two corresponding anatomical landmarks. In the graphic below adapted from Fisch (1999) by minaanandag, each midline site is 10% or 20% of the distance from the nasion to the inion.

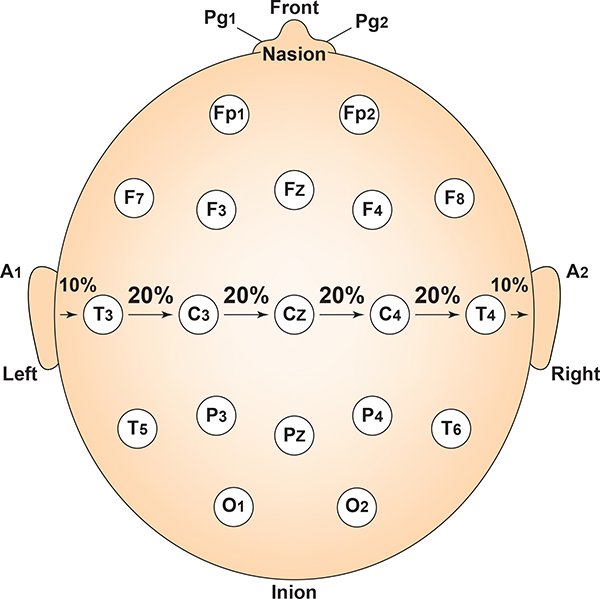

Each horizontal axis site is 10% or 20% of the distance from the two preauricular points. Graphic adapted from Fisch (1999) by minaanandag.

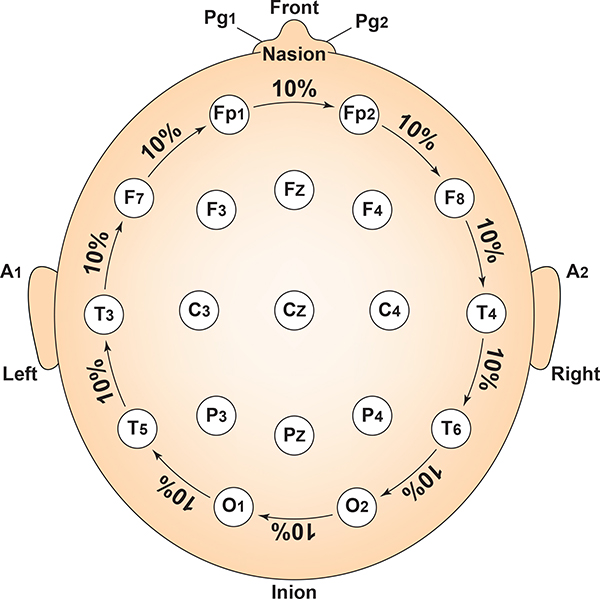

Each circumferential site is 10% of the total circumference, excluding Fpz or Oz. Graphic adapted from Fisch (1999) by minaanandag.

Intermediate sites are halfway between sets of adjacent sites. Graphic adapted from Fisch (1999) by minaanandag.

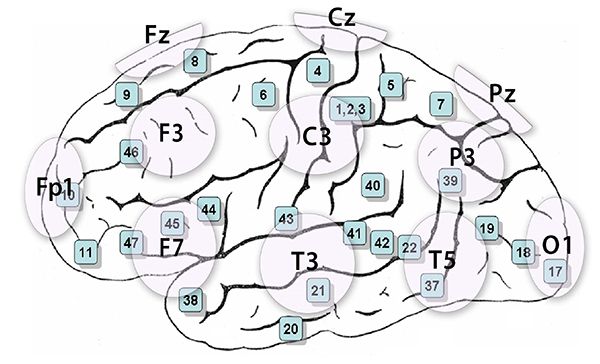

The graphic by Dailey (2013) shows the correspondence between 10-20 sites and Brodmann areas, which are 47 numbered cytoarchitectural zones of the cerebral cortex based on Nissl staining.

The 10-20 system assigns recording electrodes a letter and subscript. The letters represent the underlying region and include Fp (frontopolar or prefrontal), F (frontal), C (central), P (parietal), O (occipital), and A (auricular). A subscript of z represents a midline (central axis from nasion to inion) placement.

Numerical subscripts range from 1-8 and increase with distance from the midline. The 10-20 system assigns odd-numbered recording electrodes on the left and even-numbered electrodes on the right side of the head. Two reference electrodes are usually placed on the earlobe. John Balven adapted the diagram below from Fisch (1999).

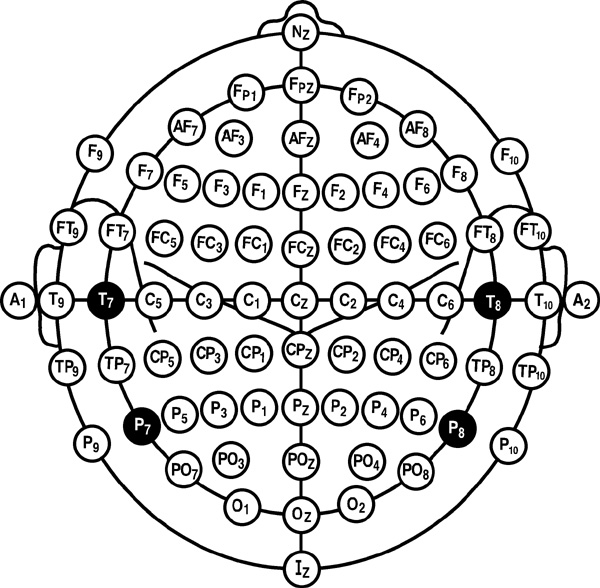

Modified Combinatorial Nomenclature

The American Clinical Neurophysiology Society published guidelines for expanding the 10-20 system to 75 electrode sites. This system, while more complex, also allows us to define more precisely the placement sites for our electrodes.The expansion of the 10-20 system allows clinicians to define the sites midway between two 10-20 sites commonly used in clinical practice, better localize epileptiform activity, increase EEG spatial resolution, and improve detection of localized evoked potentials. The modified combinatorial system replaces inconsistent designations (T3/T4 and T5/T6) with consistent ones (T7/T8 and P7/P8). Black circles depict these replacement sites with white lettering in the diagram below.

The modified combinatorial system, which is also called the 10-10 system, locates electrodes at every 10% along medial-lateral contours and adds new contours. Each electrode site is an intersection between a medial-to-lateral coronal line (designated by letters) and a longitudinal sagittal line (designated by numerical subscripts).

As with the 10-20 system, letters represent the underlying region and include: N (nasion), Fp (frontopolar or prefrontal), AF (anterior frontal), F (frontal), FT (frontotemporal), FC (frontocentral), A (auricular), T (temporal), C (central), TP (temporal-posterior temporal), CP (centroparietal), P (parietal), PO (posterior temporo-occipital or parieto-occipital), O (occipital), and I (inion). FT and FC lie along the second intermediate coronal line, TP and CP along the third, and PO along the fourth.

A subscript of z represents a midline (central axis from nasion to inion) placement. Numerical subscripts range from 1-10 and increase with distance from the midline. The modified combinatorial system assigns odd-numbered recording electrodes on the left, and even-numbered electrodes on the right side of the head David Kelsey adapted the diagram below from Fisch (1999).

Comparison of Neuroimaging Techniques

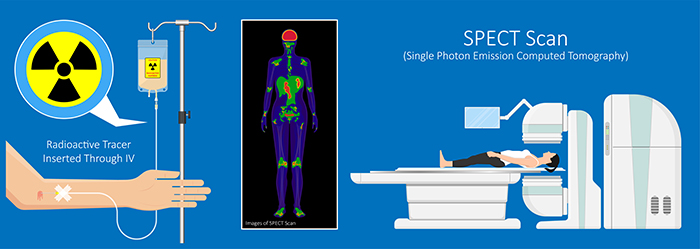

Neuroimaging methods can be thought of as either structural or functional. Structural methods include CT and MRI and present images of brain structures. Functional methods include EEG, MEG, fMRI, PET, and SPECT, each of which constructs images showing the location of differing levels of brain activity.

The different functional neuroimaging methods use different biologic signals as their index of function. EEG and MEG use brain electrical activity, fMRI uses blood oxygen level, PET uses positron-emitting radioisotopes bound to glucose, and SPECT uses gamma-emitting radioisotopes. Therefore, PET and SPECT are more invasive and pose more significant risks to patients and research participants (Breedlove & Watson, 2020).

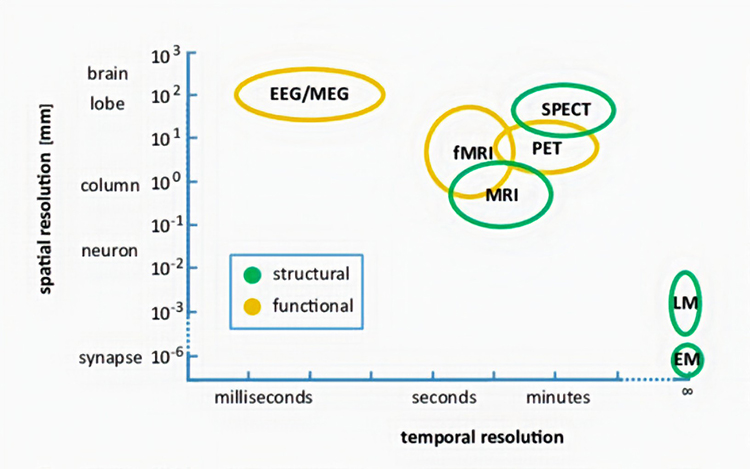

Each functional neuroimaging method can be rated with respect to how quickly it can detect changes in function (temporal resolution) and over how small an area it detects changes in function (spatial resolution). Whereas EEG and MEG methods detect changes in function most quickly, they are less able to detect the precise area where functional changes occur compared to fMRI. Graphic from Pfister et al. (2012) © Mathematics and Visualization. EM = electron microscope and LM = light microscope.

STRUCTURAL TECHNIQUES

The main structural imaging techniques are computerized axial tomography and magnetic resonance imaging.Computerized Axial Tomography

Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT or CT) provides medium-resolution images of brain structure by moving an x-ray source along an arc surrounding the head (Breedlove & Watson, 2020). Watch the Blausen CAT Scans animation. Graphic © Tyler Olson/Shutterstock.com.

CT scans allow physicians to visualize structural abnormalities like stroke damage and tumors. Graphic © Triff/Shutterstock.com.

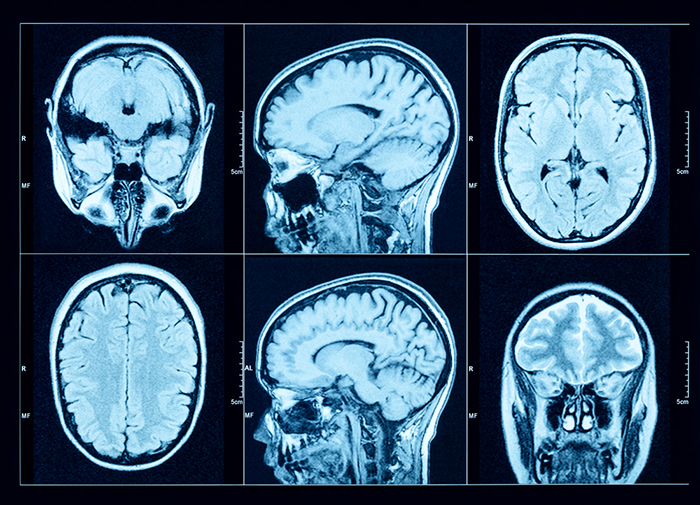

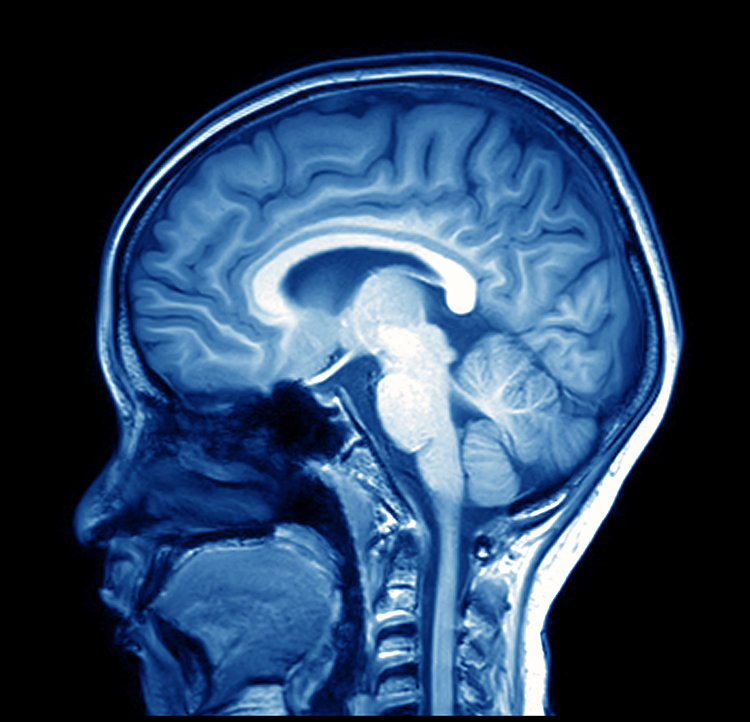

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) constructs higher-resolution images than CT scans. Since MRI scans use powerful magnetic fields and radio wave pulses to construct images of living brains, they are safer than CT scans because there is no radiation exposure. MRI scans allow a detailed examination of brain topography, including the location and volume of specific brain regions. Graphic © Peastock/Shutterstock.com.

MRI scans' superior spatial resolution can detect demyelination in disorders like multiple sclerosis that CT scans would miss (Breedlove & Watson, 2020). Graphic © MriMan/Shutterstock.com.

FUNCTIONAL TECHNIQUES

Functional techniques reviewed in this section include the EEG and qEEG, magnetoencephalography (MEG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single-photon computerized emission tomography (SPECT). See Lebby (2013) for an excellent overview of these techniques. Also, consult the McGill brain imaging tool module.EEG

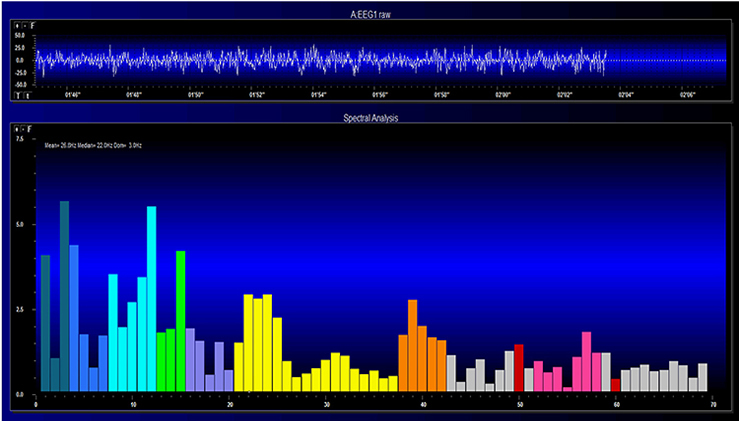

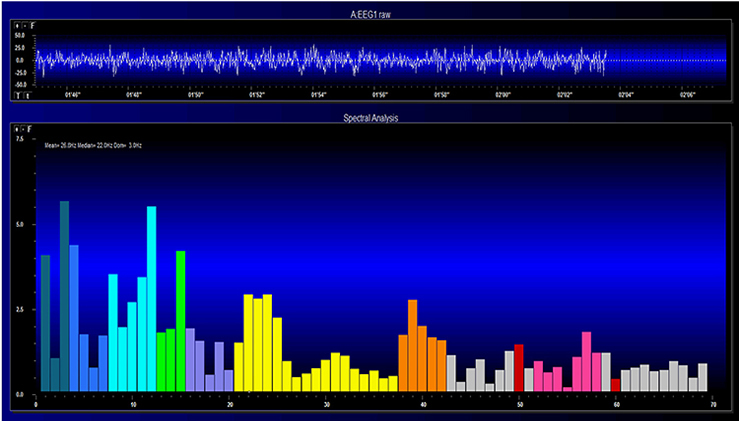

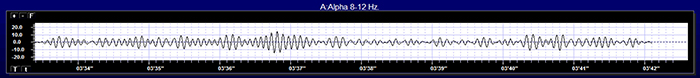

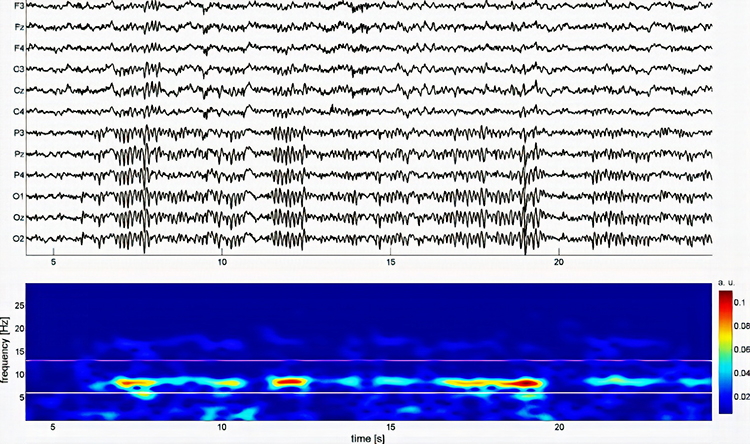

EEG and qEEG can be conceptualized as functional imaging techniques. A single-channel EEG performs “neuroimaging” by displaying an image of microvolts in adjacent 1-Hz bins or adjacent bands (e.g., a 2D spectrogram (shown below) or with a 3D spectrogram. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

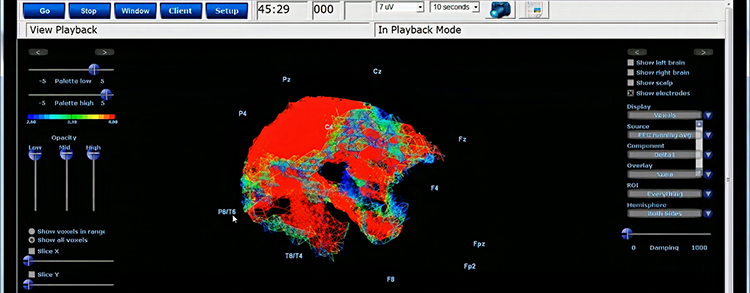

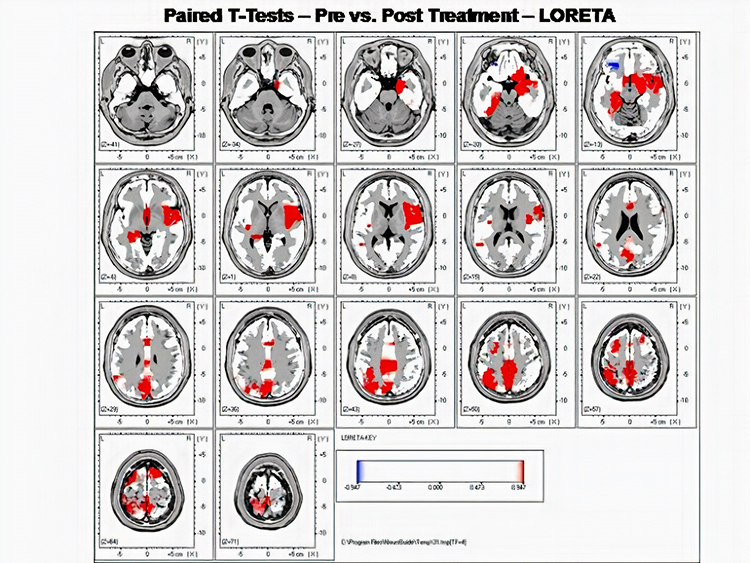

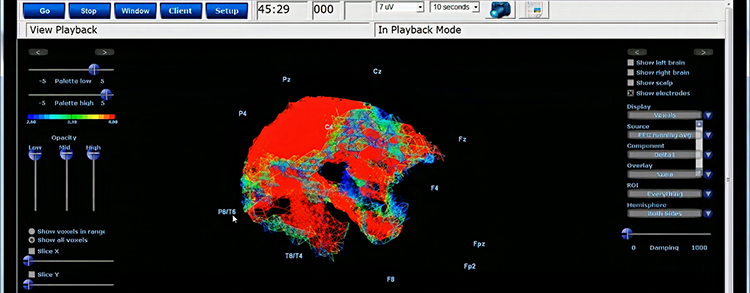

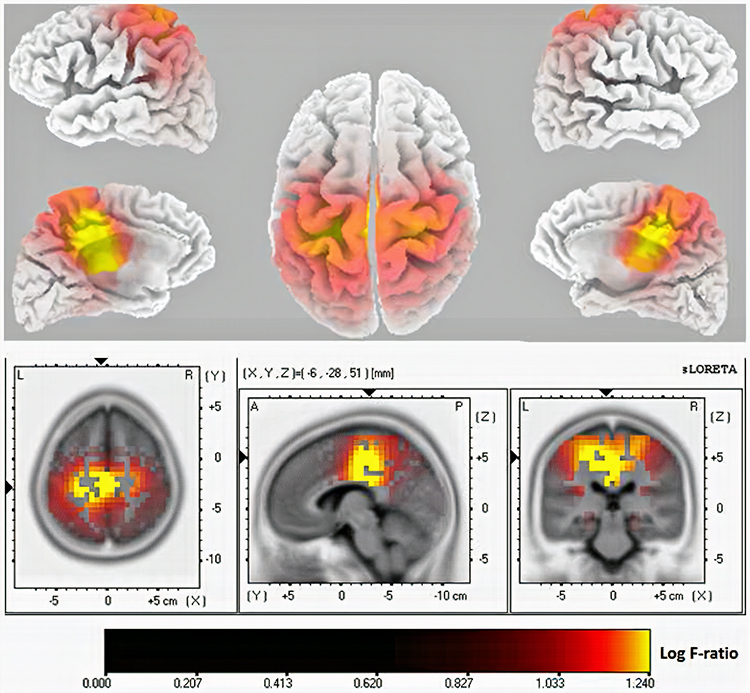

Further, 19-channel qEEG methods show images of activity as it is distributed across the brain’s convexity (i.e., over a 2D 10-20 map) or in 3 dimensions using more advanced qEEG methods (e.g., LORETA). Graphic courtesy of BrainMaster Technologies.

Magnetoencephalography

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) is a noninvasive functional imaging technique that uses SQUIDs (superconducting quantum interference devices) to detect the weak magnetic fields generated by neuronal activity. As with the EEG/qEEG, spatial resolution is inferior (cm compared to mm) to the functional MRI (fMRI) (Breedlove & Watson, 2017). Graphic © Steve Shoup/Shutterstock.com.

MEG's millisecond temporal resolution allows it to measure rapidly shifting patterns of cortical circuit activation (Breedlove & Watson, 2020). Researchers may combine MEG with MRI to better delineate the cortical structures generating the magnetic fields (Lin et al., 2004). The MEG graphic below is courtesy of the University of Montreal MEG Laboratory website.

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)generates intense magnetic fields to detect brain regions' oxygen use during specific tasks indirectly.

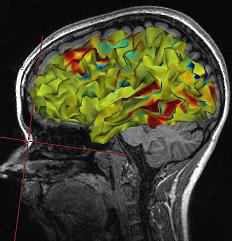

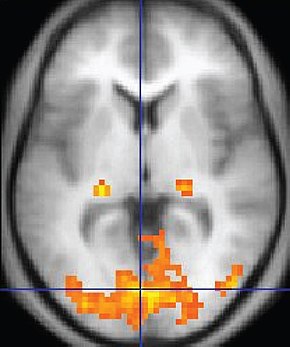

fMRI images represent communications from other neurons and changes in local potentials instead of action potentials. Although the fMRI is limited by significant (100-ms to several-s) delays, it can reveal network contribution to cognitive performance. The fMRI trades spatial resolution for PET's superior temporal resolution (Breedlove & Watson, 2020). A fMRI image © Wikipedia is shown below.

Watch the Blausen MRI animation.

Positron Emission Tomography

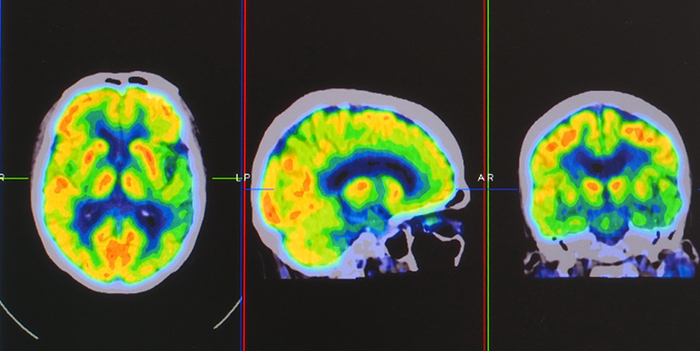

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a functional imaging technique that injects radioactive chemicals into the brain's circulation to measure brain activity (Breedlove & Watson, 2020).

PET scans achieve low temporal resolution (seconds to minutes) with moderate spatial resolution. PET images © Yok_onepiece/Shutterstock.com are shown below.

Single-Photon Emission Computerized Tomography

Single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) is a functional imaging technique that uses gamma rays to create three-dimensional, and slice images of cerebral blood flow averaged over several minutes. Graphic © rumruay/Shutterstock.com.

SPECT achieves limited temporal (minutes) and spatial resolution (centimeters).

Using a Limited Number of Electrodes

Peer-reviewed evidence suggests that more EEG channels provide a more accurate assessment and achieve superior clinical or performance outcomes compared with fewer channels (Lau et al., 2012).

Although some practitioners conduct assessment and training with a single channel, assessments and training methods that use more than one channel have become more available. For example, the cost of a full 19-channel EEG assessment has decreased substantially. Such an assessment can provide not only EEG amplitude data from all sites in the 10-20 system but additionally makes calculations of metrics such as coherence and phase that give information on how well the 10-20 sites communicate with each other. These data from multi-channel methods are beneficial for complex symptom profiles like those associated with Autism Spectrum Disorders, epilepsy, and traumatic brain injury (Thompson & Thompson, 2016). Graphic © Chaikom/Shutterstock.com.

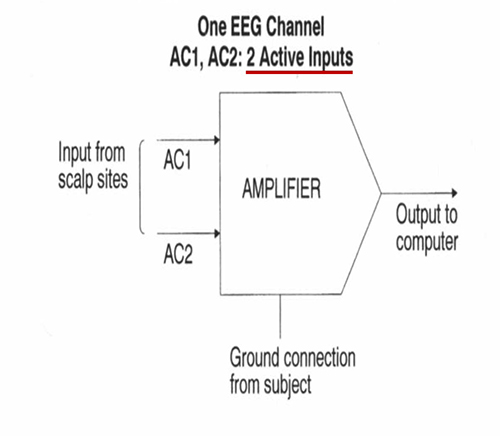

A channel is an EEG amplifier output that is the result of scalp electrical activity from three electrode/sensor connections to the scalp. These sensors are commonly known as active, reference, and ground electrodes, though they are more appropriately called positive +, negative - and reference. They are placed on the head in the following manner: an active or positive electrode is placed over a known EEG generator like Cz. A reference or negative electrode may be located on the scalp, earlobe, or mastoid. A ground/reference electrode may also be placed on an earlobe or mastoid (Thompson & Thompson, 2016).

Active and reference sensors are identical balanced inputs and interchangeable. However, some neurofeedback data acquisition systems require the designation of a specific sensor as a "reference," as in a linked-ears reference.

A derivation is the assignment of two electrodes to an amplifier's inputs 1 and 2. For example, Fp1 to O2 means that Fp1 is placed in input 1 and O2 in input 2.

A montage groups electrodes together (combines derivations) to record EEG activity (Thomas, 2007).

All montages compare EEG activity between one or more pairs of electrode sites.

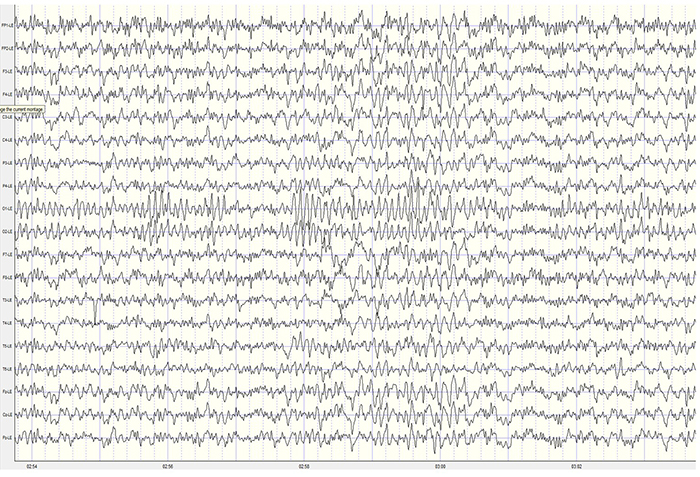

Modern amplifiers record all input sensors in reference to a common sensor - often Cz - and all montage (sensor comparison) changes are performed in the software. Amplifiers no longer require manual switching of electrodes between inputs.The narrated video below © John S. Anderson displays the same 21-channel recording viewed using different montages with a 60-Hz notch filter on and off.

Montage Options and Their Consequences

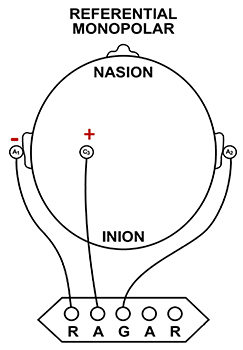

Referential (Monopolar) Montage

A referential (monopolar) montage places one active electrode (A) on the scalp and a "neutral" reference (R) and ground (G) on the ear or mastoid. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

A referential montage assumes that the EEG activity seen on the computer screen represents the active (+) site because the reference (-) site is assumed to be neutral (i.e., producing no EEG activity) and because of the subtraction of signals produced by noise and artifacts that are common to both active and reference sites (common-mode rejection). In the photograph below, the blue cable would be used for the active electrode, the yellow cable with an ear clip for reference, and the black cable with an ear clip for the ground.

However, this montage is vulnerable to artifact from the contraction of facial muscles (Demos, 2019). The ear reference is also known to produce reference contamination, where EEG signals from this electrode are contributed or added to other electrodes via the mechanism of the differential amplifier, where anything different between the "active" and "reference" sensors is retained. This commonly results in alpha activity produced by posterior sources of alpha that are close to the ear.

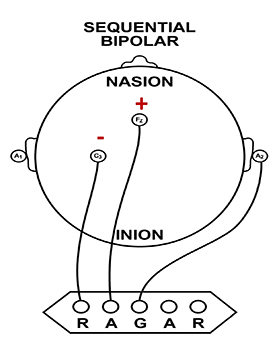

Sequential (Bipolar) Montage

A sequential (bipolar) montage presents a sequence of comparisons of positive (+) and negative (-) electrodes (often called ‘active’ and ‘reference’) that are attached to sites on the scalp and therefore considers the reference electrode to be a second active electrode. The ground (G) electrode is attached to the scalp, to an earlobe, or over the mastoid process. Graphic © John S. Anderson.

The sequential montage detects the difference in EEG between the positive and the negative electrodes (active and reference), as the referential montage does. Still, now the signal for the channel represents the difference between two sources of EEG activity. In cases when 19-channels are used, this montage is usually presented with electrode pairs shown in sequence. In the photograph below, note that only the black cable for the ground has an ear clip.

When used as only a single channel, this montage does not allow good detection of localized EEG activity because it shows only the difference between the A and R signals. However, when used as part of a 19-channel assessment, it localizes EEG events related to epilepsy. This montage can also reduce artifact when the A and R electrodes are relatively close together.

A sequential montage is frequently used in neurofeedback and trains the difference between EEG activity at the A and R electrodes. However, when neurofeedback training produces a change, it remains uncertain whether it is because of a change in EEG at the A electrode, the R electrode, or both electrodes.

The EEG record appears more similar when sensors are closer together and less similar when they are farther apart (Fp1-O2). When electrodes are spaced close together (Fp1-Fp2), this montage may reject actual EEG activity (Fp1-Fp1). Graphic © John S. Anderson.

Recognizing and Correcting Signals of Noncerebral Origin

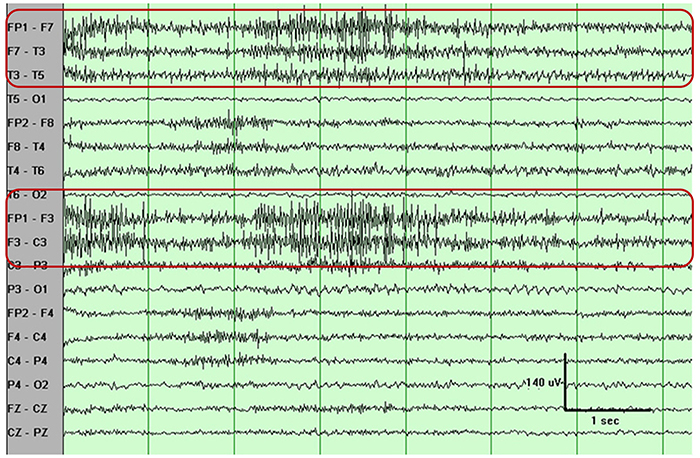

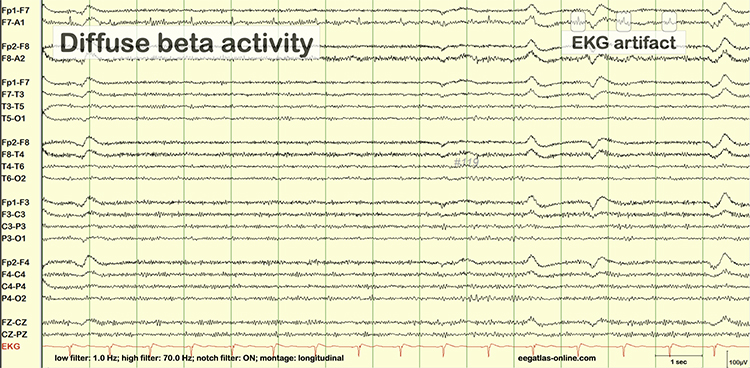

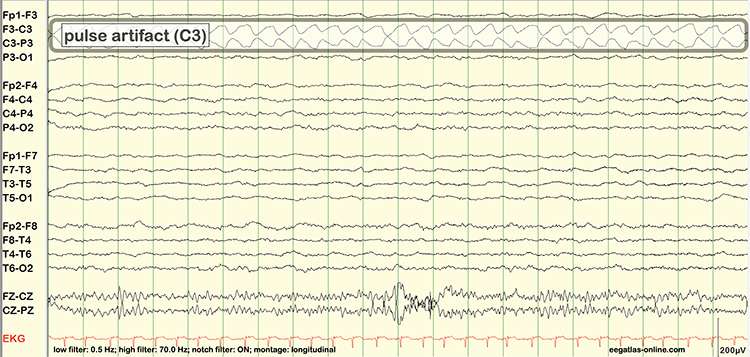

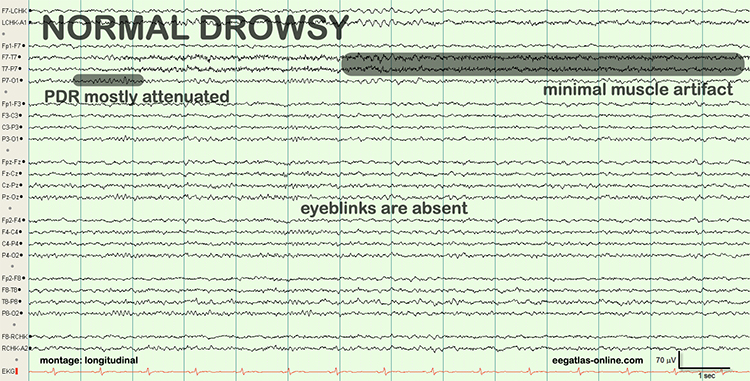

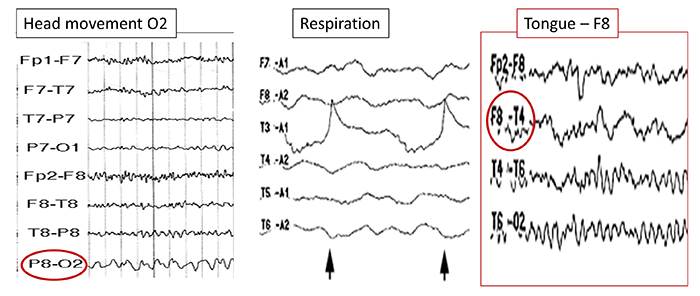

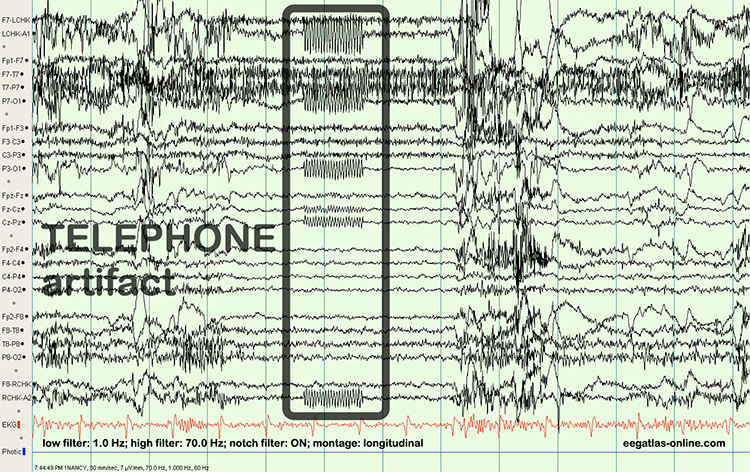

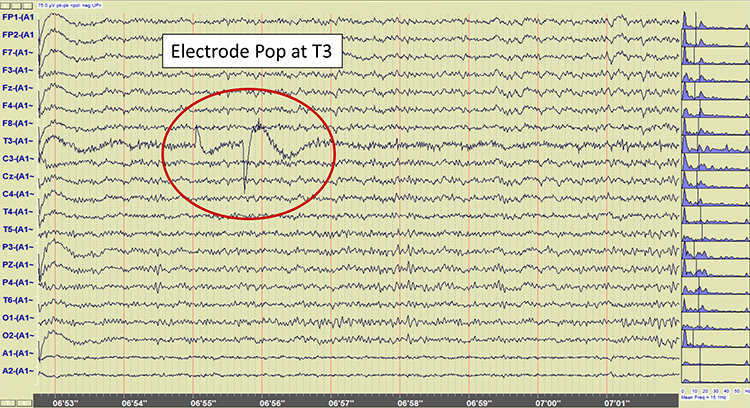

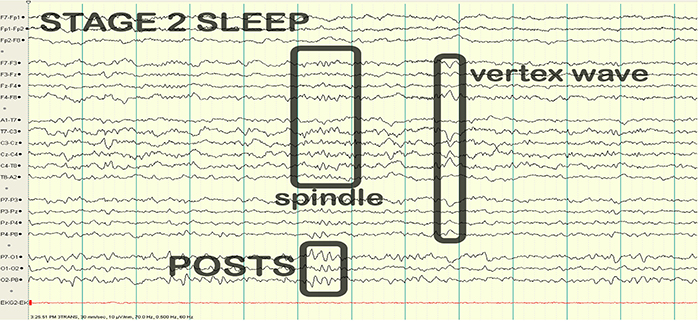

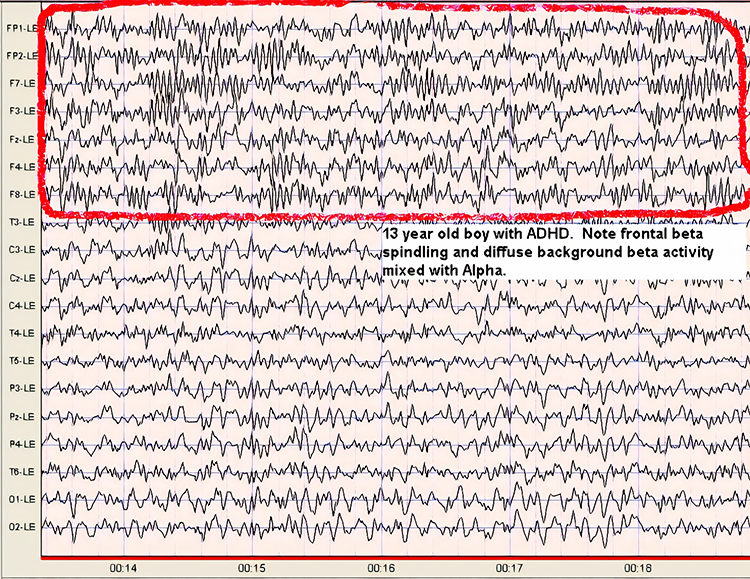

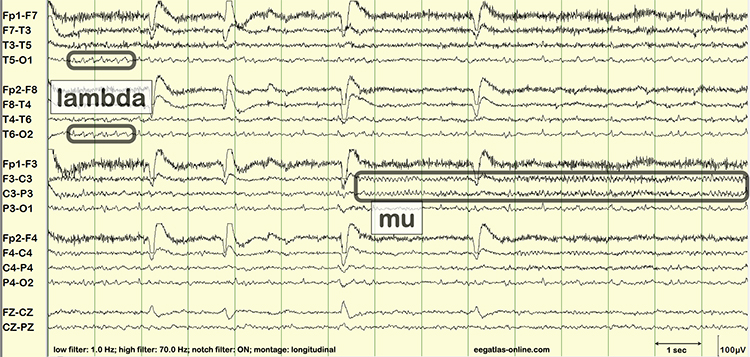

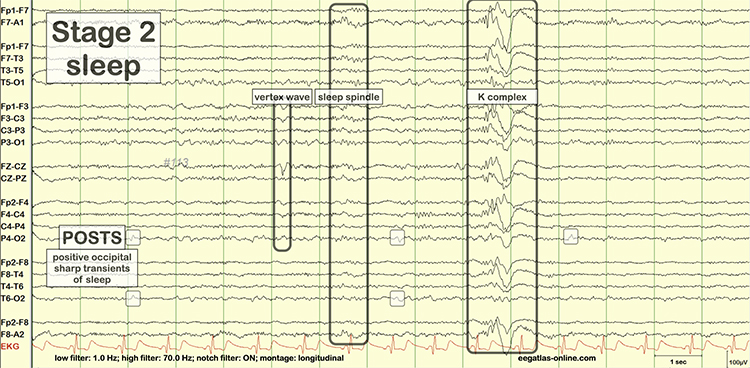

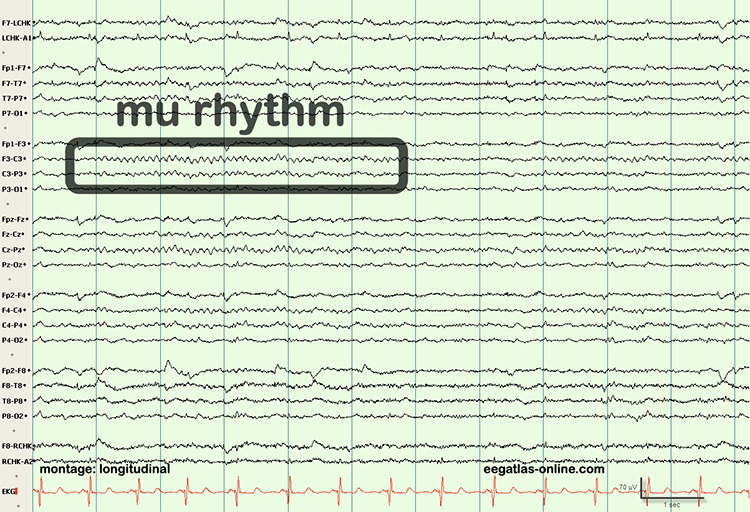

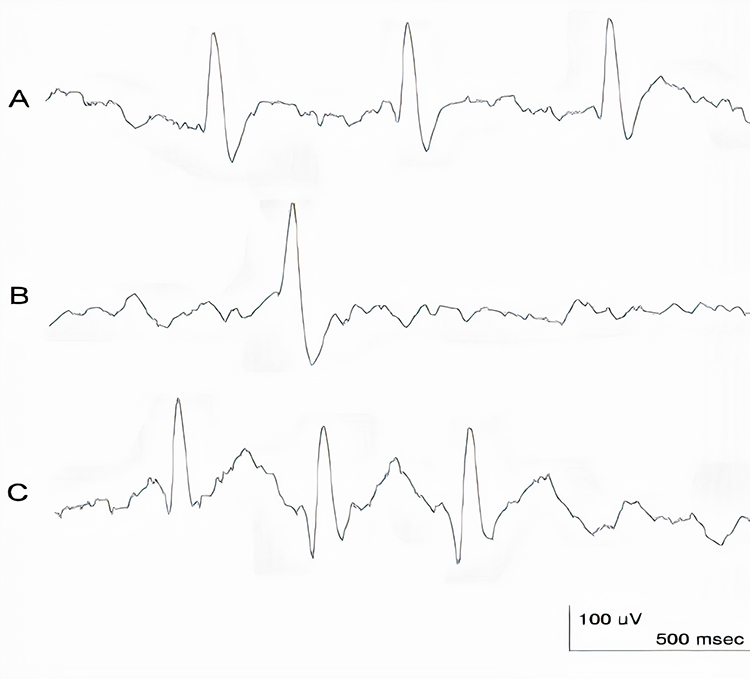

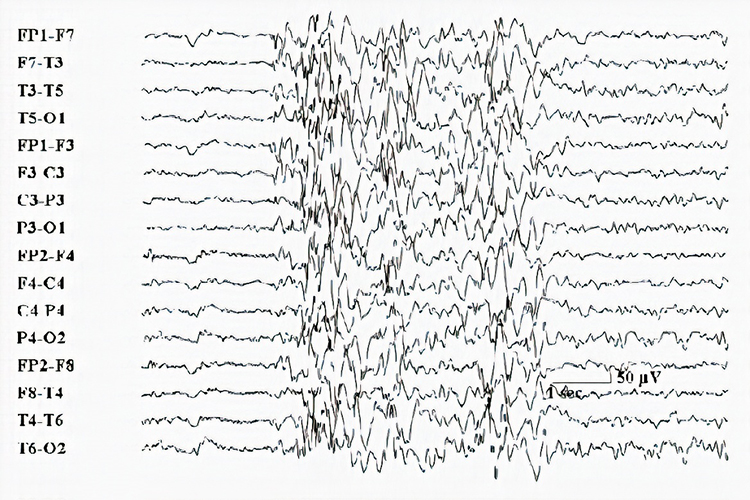

EEG artifacts, which consist of noncerebral electrical activity, can be divided into physiological and exogenous artifacts. Physiological artifacts include electromyographic, electro-ocular (eye blink and eye movement), cardiac (pulse), sweat (skin impedance), drowsiness, and evoked potential. Exogenous artifacts include movement, 60 Hz and field effect, and electrode (impedance, bridging, and electrode pop) artifacts.

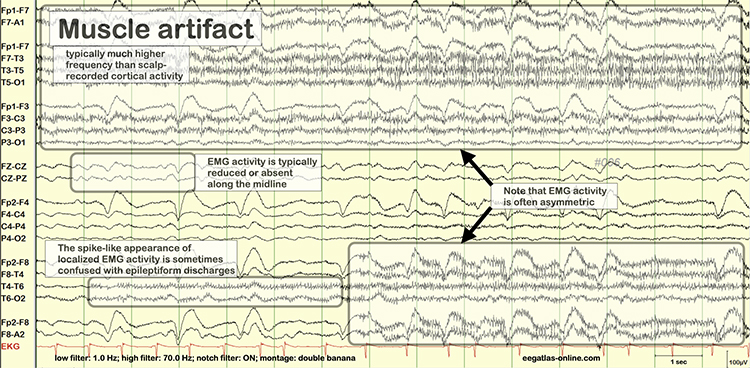

Electromyographic (EMG) Artifact

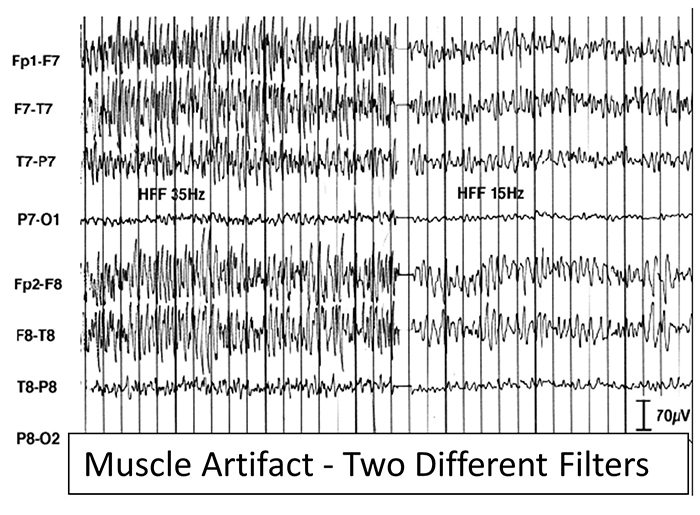

EMG artifact is interference in EEG recording by volume-conducted signals from skeletal muscles. This artifact contains high-frequency activity that resembles a "buzz" of fast activity during a contraction. EMG is seen as fast beta activity in the qEEG. While some frequencies are between 10-70 Hz, most are 70 Hz or higher.The graphic shows how high-frequency filter (HFF) selection can affect contamination by this artifact. A high-frequency filter (low-pass filter) attenuates frequencies above a cutoff frequency. In the examples below, the cutoffs are 35 Hz and 15 Hz.

All the channels on the left side of the tracing show SEMG artifact admitted by a 35-Hz high-frequency filter. The right tracing is free from SEMG artifact since its 15-Hz high-frequency filter attenuates the higher frequencies that contain this artifact.

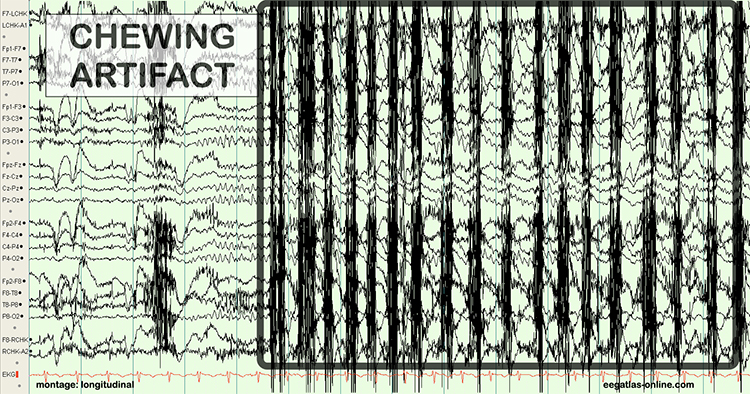

The next graphic shows how gum chewing can generate SEMG artifact by contracting the muscles of mastication. Graphics © eegatlas-online.com.

The frequency spectrum for SEMG artifact ranges from 2-1,000 Hz. While strong muscular contraction can contaminate all frequency bands, including 10 Hz, the beta rhythm (at 70 Hz or higher) is most affected by this artifact. EMG artifact may create the appearance of greater beta activity than is present. Graphic © eegatlas-online.com.

Below is a BioGraph ® Infiniti EMG artifact display. Note how the amplitude of the EEG spectrum increases with each contraction.

Thompson and Thompson (2016) observed that EMG artifact is readily detected because it affects one or two channels, particularly at T3 and T4 at the periphery, and less often at O1, O2, Fp1, and Fp2.

You can identify EMG artifact by visually inspecting the raw signal. The next graphic shows SEMG artifact using a 70-Hz high-frequency filter.

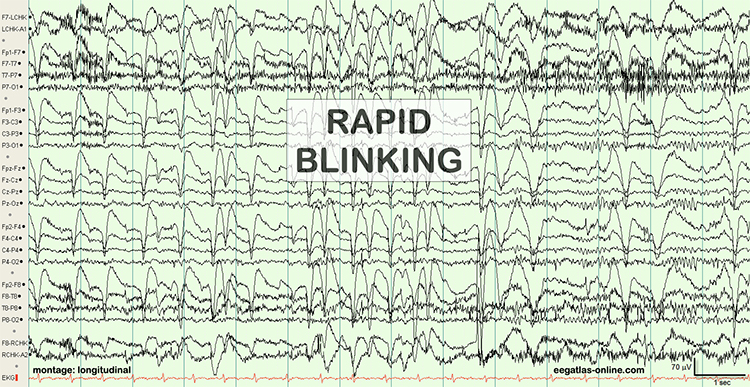

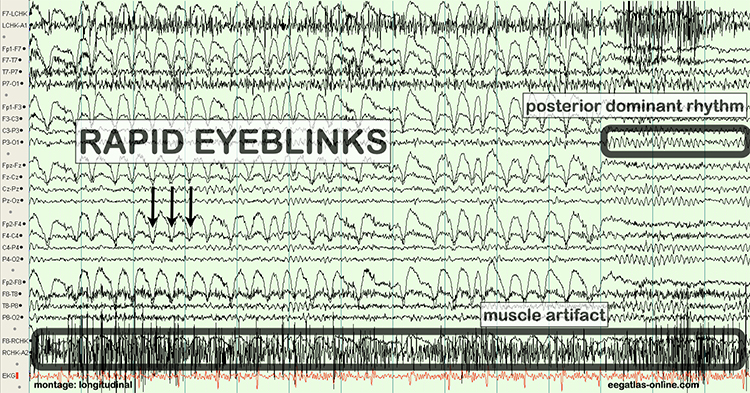

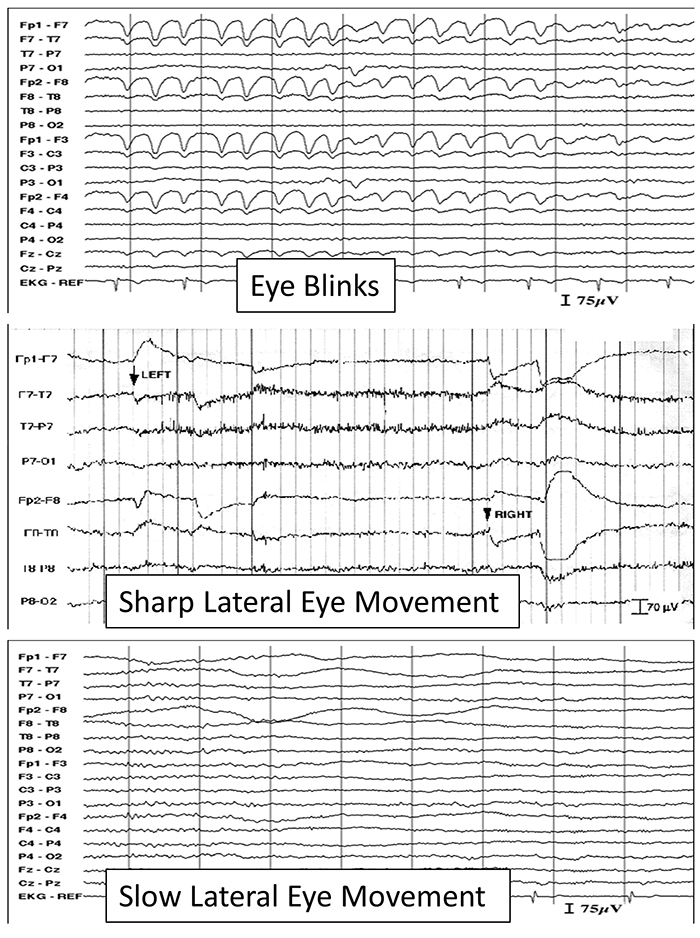

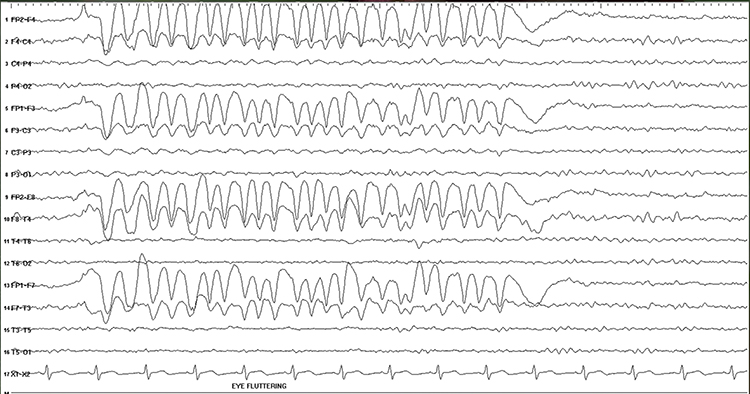

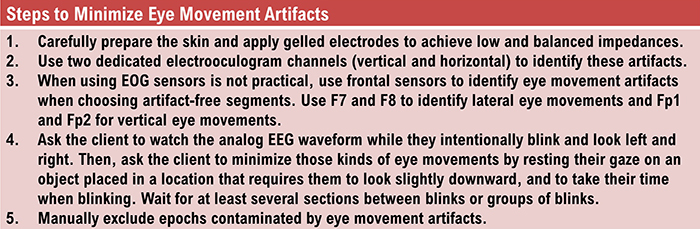

Electro-Ocular Artifact

Electro-ocular artifact contaminates EEG recordings with potentials generated by eye blinks, eye flutter, and other eye movements. For example, anxious patient eyelid flutter may cause deflections at Fp1 and Fp2 (Klass, 2008).This artifact is due to the movement of the eye’s electrical field when the eye rotates and the contraction of the extraocular muscles. The eye creates a dipole that is electropositive at the front and electronegative at the back. Bell’s Phenomenon refers to the upward rotation of the eye when it closes and causes an artifact seen as an apparent increase in EEG.

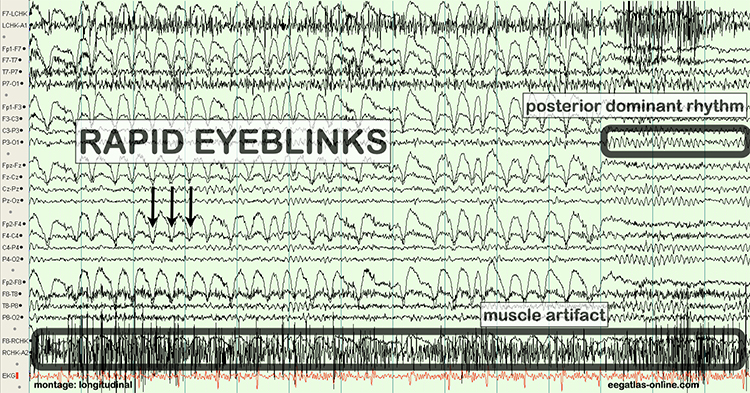

The next two graphics show eye movement artifact due to rapid blinking. Graphics © eegatlas-online.com.

The next graphic shows eye blinks, sharp lateral eye movement, and slow lateral eye movement.

Below is a BioGraph ® Infiniti EEG display of eye movement artifact.